Simon Thompson looks at the ten best director’s cuts that improve on the original theatrical editions…

Director’s cuts are a strange beast indeed. Some of them completely enhance or make amends for the initial movie’s strengths and/or short-comings, but others usually add far too much water to a perfectly good beer (cough… Apocalypse Now Redux…cough) and accord a great deal of hype and fanfare to what, is essentially, a deleted scenes section.

The ten movies on this list however, are very much examples of director’s cuts which are the superior versions of their respective director’s work, and are often considered by fans and critics to be the one true version of the movie.

Brazil (1985)

Terry Gilliam is one of American cinema’s great iconoclasts, a savvy and uncompromising auteur who has constantly had to fight tooth and nail with studio executives and money men to bring his artistic visions to the screen in the way that he intended them to be.

One of the most prominent examples of this dynamic in Gilliam’s career was the constant interference by Universal during the making of his darkly comedic Orwellian science fiction masterpiece Brazil. Despite the fact that the movie is a despondent satire of bureaucracy and authoritarianism, complete with a tonally consistent depressing ending (in homage to 1984), Universal executive Sid Sheinberg secretly produced a 94 minute cut from the initial 142 minute print of the movie, with a tacked-on happy ending, in a bid to make the movie more commercially viable.

This cut has come to be known as The Love Conquers all version by fans of Brazil and it has justifiably gained a reputation amongst movie-buffs for being a flagrant bastardisation of Gilliam’s intent. After a back and forth between Gilliam and Sheinberg, Gilliam released a 132 minute cut closer to what he wanted for the American market. Although a decent compromise, the true version of Brazil lies in the 142 minute director’s cut, where Gilliam’s Kafkaesque nightmarish future is fully realised in all its deliberate grotesquery.

Blade Runner (1982)

Blade Runner is a movie which has undergone more changes than David Bowie. One of the most influential science fiction films ever made, it’s a beautiful synergy of Ridley Scott’s directing, Vangelis’s soundtrack, Douglas Trumbull’s timeless special effects, Hampton Fancher and David People’s script, and Syd Mead’s Metal Hurlant inspired production design-the film’s futuristic noir aesthetic being heavily inspired by Moebius and Dan O’Bannon’s 1975 masterwork The Long Tomorrow a bande dessinée (drawn strip), which is seen by many to be the genesis of cyberpunk.

Blade Runner is a despondent, cynical noir tale set in a dystopian future, which, in post Star Wars more child-friendly mass-market science fiction boom felt wildly out of place within a newly corporatized Hollywood that wanted to play it safe as much as possible.

Because of this, the movie’s producers, The Ladd Company, ordered that it needed to be re-cut with a tagged on happy ending that reused stock footage from The Shining, a voiceover was put it in place to spoon-feed the audience about the narrative and the movie’s themes and ideas as if they were children, any sort of ambiguity about the protagonist Rick Deckard being a replicant was removed, and as a result the movie bombed like crazy – making only forty one million dollars back on a budget that was over thirty million and didn’t fare particularly well with critics either.

However, the films aesthetic and whatever cynicism and ambiguity that remained in the original cut helped Blade Runner develop a huge cult following, and its aesthetic influenced both novels like William Gibson’s The Neuromancer and helped to foster a new wave of sci-fi in Japan with the likes of Akira, Battle Angel Alita, Ghost In the Shell and Bubblegum Crisis being heavily inspired by its visuals and themes.

In 1992 however, Ridley Scott gained the rights to release his director’s cut with the original ending and the ambiguity of Deckard’s status as human or replicant, with this particular version testing well at a screening of its workprint. Because of this the director’s cut was released on VHS to massive critical acclaim and newfound appreciation by audiences and critics.

Thanks to the initial release of the director’s cut on VHS in the early 90s and the later release of the final cut in 2007 as a special edition DVD, Blade Runner has now been rightfully regarded as one of the most important works in the sci-fi genre, even being preserved in the national film registry by the library of congress in America – all thanks to Ridley Scott’s gamble to release the director’s cut.

Once Upon a Time In America (1984)

Sergio Leone’s final magnum opus, the sweeping crime epic Once Upon a Time in America, is one of the most brutal yet emotionally cathartic movies you will ever come across, but since Once Upon a Time in America is my all-time favourite movie in any genre I, of course, might be more than a little biased.

A sprawling gangster epic in the vein of both The Godfather (one of the many movies Leone turned down directing during the long pre-production before he could make Once Upon a Time In America), the film tells the story of two prohibition era gangsters, played by Robert De Niro and James Woods, over a thirty odd year period, with De Niro’s character returning to New York City within the movie’s present (the 1960s) to tie up the loose ends of his youth. In the midst of this he is haunted by constant flashbacks to his poverty-stricken childhood and his violent misdeeds as an adult.

Originally running for six hours when it was shown at the Cannes film festival in 1984, European distributors of the movie managed to compromise with Leone and get him to produce a four hour version, which is the cut that was shown to European audiences and critics to widespread acclaim.

Leone’s dealings with his American distributor Warner Bros. was a lot less pleasant however, as, without his consent, they whittled the movie down to two hours and twenty minutes, presented the narrative in a chronological order and eschewed the brilliant use of flashbacks that make the movie as interesting as it is narratively, and to add further insult to injury forgot to mix in Ennio Morricone’s masterful score properly, robbing most of the movie’s poignant scenes of their full emotional impact.

While this monstrosity was the version sadly shown to general American audiences, the proper four hour European cut was thankfully screened at arthouse cinemas across the US – at least giving some sections of the American public the true version of this absolute masterpiece.

The American general release cut was so bad that Siskel and Ebert named it their joint worst movie of 1984, with the original cut by contrast being their joint best movie of 1984. Thanks to the DVD release of the director’s cut, Once Upon a Time In America has now been seen and rightfully re-appraised by American audiences for the triumph that it truly is. Sadly Leone did not live long enough to bask in this vindication, as the mammoth production of Once Upon a Time In America, when combined with his precarious health, caused him to suffer a fatal heart attack aged sixty in 1989.

In 2012 due to the collaboration of the Leone family estate with Martin Scorsese, Regency, and various other Italian subsidiaries with financial backing from Gucci, over twenty minutes of lost footage has been re-discovered and re-integrated into the original work print ( the rough version of a completed movie or tv show used during editing) with upgraded resolution of the movie’s picture to boot.

What this means is that now we thankfully live in a world where a version of Once Upon a Time In America as true to Leone’s original vision as possible, without the extra two hours missing from the Cannes cut, is widely available for audiences to see.

Leon (1994)

Cinema du look luminary Luc Besson is a filmmaker who is no stranger to having his work chopped and changed by American distributors. His masterpieces The Big Blue (1988), La Femme Nikita (1990), and The Fifth Element (1997) had huge chunks shaved out of all of them, but it’s his 1994 action revenge classic Leon that I’m going to mention on this list.

To cut a long story short, Leon tells the story of a twelve-year old girl (played by Natalie Portman), named Mathilda, who after her family is gunned down by a crazed corrupt DEA agent (played by Gary Oldman in his prime 90s bad guy era), turns to Leon (Jean Reno), a hitman who just so happens to live in her apartment building, to be taught the ways of ‘cleaning’.

Released in the US with 30 minutes cut from the original 2 hrs 10 min French version and retitled The Professional, the American version cut some of the movie’s more controversial elements – not only the incredibly contentious subtext in Leon and Mathilda’s relationship, but also various action sequences in which Mathilda is made far more complicit in Leon’s kills.

Granted, the extra scenes between Leon and Mathilda in the European cut are extremely uncomfortable to say the least, but they still add an uneasy depth and scope for debate so that removing them from the movie turns Leon into a completely different film all together.

In the case of Leon, whatever version of the movie that you prefer comes down to your subjective stomaching of some scenes that while never crossing any line damn well buy themselves a beer and pull up a deckchair near one.

Daredevil (2003)

Hell’s Kitchen’s guardian devil is my second favourite superhero behind Batman and one of Marvel’s most iconic characters of the last forty years, thanks largely in part to Frank Miller’s legendary run in the late 1970s/early 1980s ( as well as his returns to the character with the stories Born Again, Love and War, The Man Without Fear, and Elektra Lives Again etc).

Unlike Spider-Man, the X- Men, or Iron Man however, everyone’s favourite blind attorney Matt Murdock has been relatively underserved when it comes to adaptations, mainly, arguably, owing to the failure of 2003’s Daredevil starring Ben Affleck. An adaptation so panned that the excellent Netflix adaptation in 2015, which did as good a job as possible with the character, had an uphill battle to climb when it came to being accepted by fans and general audiences.

Put simply, the theatrical version of the 2003 adaptation, which was heavily cut by Fox in the aim of obtaining a PG-13 rating, is absolutely dire. Various character arcs make absolutely no sense because of the cuts, and having a neutered version of a character like Daredevil who is beloved by fans because of the grounded, gritty, and often Catholic guilt infused edge to his adventures was always going to alienate the movie’s built in audience.

Disappointed for years after seeing it, I despised this movie, alongside other Daredevil fans, for how toothless and sanitised an adaptation this was, until I discovered Mark Steven Johnson’s R-rated director’s cut which both stayed true to the stylised violence and noirish tone of the comics, as well as the plot structure actually making sense.

While Daredevil is not a perfect adaptation by any means, Mark Steven Johnson’s director’s cut still managed to perform a sea-change in fan opinion towards this movie, and with Disney+’s probable butchering of Born Again (a Daredevil story by Frank Miller so good it rivals his other classics such as The Dark Knight Returns and Sin City) coming our way soon, Mark Steven Johnson can enjoy a hearty laugh at their expense.

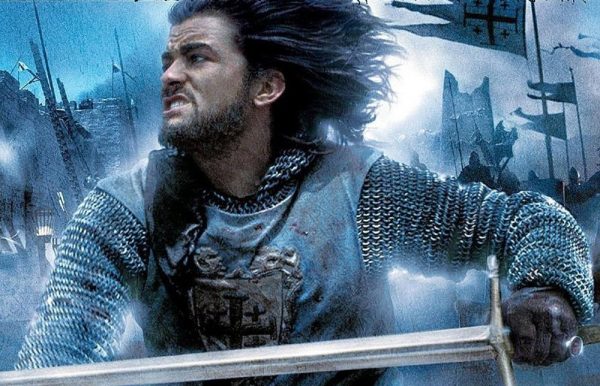

Kingdom of Heaven (2005)

Crusade set historical epic Kingdom of Heaven, the second entry on this list from director Ridley Scott, can stand in good stead alongside Blade Runner as an example of the evils of studio interference. Even though Scott was on a post Gladiator high in the 2000s, working at a level of prominence he hadn’t truly been accustomed to for well over a decade, Kingdom of Heaven still fell victim to its distributor 20th century Fox’s fears over poor test screenings. As a result Scott was forced to cut out well over forty five minutes, taking the length down from three hours and fourteen minutes to a more marketing friendly two hours and twenty four minutes.

Kingdom of Heaven is a masterfully plotted, almost novelistically in depth narrative, revolving around a series of sub plots, which, when cut from the movie, leaves it like delicious goulash without paprika. Unsurprisingly the hacked-up version bombed amongst critics and audiences upon its release.

Almost a year later, however, Scott presented his three hour cut of the movie on DVD with the movie’s narrative depth fully intact, with subplots removed from the theatrical version such as the extended character depth for both Sibylla (The Queen of Jerusalem) and her leprosy stricken son (a fate sadly shared with his father Guy De Lusignan), as well as far bloodier and more elaborate battle sequences that highlighted the sheer horror of the violence of the period, which were more than likely trimmed by Fox so that the movie could easily secure an R rating.

While the director’s cut still can’t fully remove Orlando Bloom and his performance as the protagonist Balian from the movie, the three hour cut of Kingdom of Heaven is the vastly superior way to experience the movie, with the additional narratives and extended battle sequences giving the movie a Homeric quality almost on a par with David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia.

Aliens (1986)

Up until recently with the release of Avatar 2, James Cameron had as much of a knack for getting sequels right as anybody in movie history. After the surprise runaway success of a little independent movie turned pop culture phenomenon, The Terminator, in 1984, James Cameron showed himself to be one of the most exciting young directors to come along since the likes of Steven Spielberg and because of this he was brought on by producer Gale Ann Hurd to write and direct the sequel to Alien.

To cut a long story short, Cameron wrote and directed a horror-science fiction masterpiece, with Aliens being as suspenseful and atmospheric as the original, but with an even stronger emphasis on action and spectacle. Cameron’s script adeptly managed to both balance the character development of Ellen Ripley, the protagonist of the series, following the events of Alien, as well as to create one of the best supporting cast of characters a single movie has ever had, with the Colonial Marines, the android Bishop, and Newt.

Aliens wasn’t as badly interfered with by its distributor as a lot of the other movies on this list were, but Cameron was still obliged to cut his preferred two hours and twenty five minute version of Aliens down to a tighter two hours and seventeen minutes.

While that might not seem like such a big difference at first glance, the missing footage that didn’t make its way back into the movie until its various home video releases adds far more character development to Ripley, Newt, and the colonial marines and was cut by Fox because they thought it slowed down the action. While the theatrical cut of Aliens is still excellent, the Cameron-approved two hours and twenty five minute version is still the way to go as it completely silences the argument that Alien is the superior of the two.

The Lord of the Rings Trilogy Extended Editions (2001-2003)

The Lord of the Rings trilogy is the perfect encapsulation of the phrase lightning in a bottle. From the time when JRR Tolkien’s magnum opus was first published, directors salivated at the chance of getting to adapt one of the single most influential fantasy series in the history of the genre, but it wasn’t until the late 1990s when New Zealand filmmaker Peter Jackson, hot off the heels of the critical acclaim of his film Heavenly Creatures, would acquire the rights to give the story the big budget live action Hollywood treatment that Tolkien’s work so richly deserved.

The end result would prove to be one of the most popular and critically acclaimed movie trilogies of all time – pulling off the rare feat of storming box office records and being nominated for Oscars at the same time.

Due to the sheer depth of narrative within The Lord of the Rings, Peter Jackson realised that he would have to slim down each of the three movies into a more palatable length for cinema audiences, with The Fellowship of the Ring being cut down from three hours and twenty eight minutes to two hours and fifty eight minutes, The Two Towers being slimmed from three hours and forty six minutes to two hours and fifty nine minutes, and Return of the King being trimmed from four hours and twelve minutes to three hours and twenty minutes.

The difference between the theatrical cuts and the extended editions in this case is akin to getting the meat and potatoes of a story versus reading the various asides and footnotes that give it more flavour.

Of the three movies, The Two Towers theatrical cut is the most perfectly acceptable one to watch as what is lost isn’t fully essential, but of The Fellowship of the Ring and The Return of the King the inclusion of the extended scenes, showing additional character development for Faramir and Galadriel in the gifting ceremony, as well as more time being afforded to Aragon’s dealings with the oath breakers and a full resolution of Saruman’s arc, make both these films the definitive viewing experience that if you love the LOTR trilogy you owe it to yourself to see.

Touch of Evil (1958)

Orson Welles’ place in film history is already as entrenched as it gets by the strength of his debut Citizen Kane alone, but, incredibly, after that one of Americas great artists was rarely given final cut by any studio that he ever worked for.

While Welles’ follow up to Citizen Kane, the literary adaptation The Magnificent Ambersons, is probably the most notorious of his various battles with studio meddling, with over forty minutes, including the ending, being chopped and changed without Welles’ consent, sadly the cut footage for that film is now an ash pile due to it being destroyed in the RKO archives.

In picking a Welles movie for this list, however, I decided to use A Touch of Evil because, while the theatrical cut of the movie at one hour and forty eight minutes is passable, the Welles-approved two hour cut is where the quality of the film is truly magnified. Welles’ preferred, and decades ahead of its time, method of cross cutting each of the narrative strings and eschewing the traditional three act structure was nixed by Universal, which made the theatrical cut both insulting and patronising due to their demand that assistant director Harry Keller shoot more expository scenes informing the audience of the plot.

To add insult to injury, Universal also decided to interrupt one of the most iconic tracking shots in movie history with Henry Mancini’s score and obstructive title cards, instead of keeping it without titles and with diegetic sound as Welles had wished.

Although these might sound like only moderate changes, when you see Welles’ approved version the extent of Universal’s hatchet job on the movie quickly dawns on you, leaving in the viewer’s mind the everlasting question of whether Touch of Evil would have been better received upon its release in 1958 if they had just let Welles get on with his original plan.

Metropolis (1927)

Fritz Lang’s silent era sprawling science fiction epic Metropolis, is, without a shadow of a doubt, one of the most influential films within the genre. Pioneering the concepts of dystopian futures, androids and artificial intelligence as well as producing sets and practical effects that were decades ahead of their time, Metropolis has influenced everybody from George Lucas to Ozamu Tezuka, David Bowie, Freddie Mercury, Motorhead, Kraftwerk, Janelle Monae, Madonna, and Sepultura. Countless illustrators, filmmakers, and musicians have been taken with its stylised, art deco tinged visuals since its release nearly a century ago in 1927.

Despite the film’s reputation as a science fiction classic today, at the time of its release it was seen by the critics as a self-indulgent flop, accusing the movie’s plotline of struggling workers overthrowing a futuristic oligarchy of being communist in tone.

After the complete two hours and thirty three minutes version premiered in Berlin by Fritz Lang ended up being lost, various editors and archivists had a crack at re-editing the available print cut for German cinema release, or finding the premiere cut, with little or no success. Various versions of Metropolis were re-cut with available footage and new soundtracks over the years, most famously with Giorgio Moroder’s Hauge visit version in 1984 (for which he outbid David Bowie by a hundred thousand dollars to obtain the rights) adding a strange colour tint and replacing the atmospheric and moody classical style with obtrusive synth, earning him two Razzies for his trouble.

In 2001 new footage of Metropolis was discovered in Buenos Aires that helped the general release cut to make more sense. Despite this allowing people to see more of Lang’s original cut as he would have intended, it wouldn’t be until nine years later, in 2010, when a further eleven missing scenes were found in a New Zealand print of the movie, allowing both versions to be spliced together to create an edition now known as The Complete Metropolis – clocking in at two hours and twenty eight minutes.

Put simply, this version of Metropolis is the Holy Grail, it both manages to give the movie a stronger plot structure as well as affording more depth to the many supporting characters, such as the Thin Man, who in the original cut, is little more than a glorified butler to Abel the madman who rules the city. The additional scenes give the movie a proto film noir quality, a sub-genre that Fritz Lang would later pioneer. The restored footage also featured beautifully cleaned up visuals and a newly remastered version of Gottfried Huppertz’s score, allowing future generations of film fans to fully appreciate Lang’s perceptive and groundbreaking masterwork in a manner that would have been unthinkable even thirty years ago.

What are your favourite director’s cuts? Let us know on our social channels @FlickeringMyth…

Simon Thompson