Though we aim to discuss a wide breadth of films each year, few things give us more pleasure than the arrival of bold new voices. It’s why we venture to festivals and pore over a variety of different features that might bring to light some emerging talent. This year was an especially notable time for new directors making their stamp, and we’re highlighting the handful of 2024 debuts that most impressed us.

Below, one can check out a list spanning a variety of different genres, and many are available to stream here. In years to come, take note as these helmers (hopefully) ascend.

Allen Sunshine (Harley Chamandy)

Directed with a sense of tranquil serenity and grounded maturity one might be accustomed to finding in the work of a seasoned director, Allen Sunshine is, quite remarkably, the debut feature of 25-year-old Harley Chamandy. The Montreal-born, New York-based filmmaker received the 2024 Werner Herzog Film Prize for his feature following its Munich Film Festival premiere earlier this year. Having participated in Herzog’s workshop as a 17-year-old, Chamandy’s shared affinity with the legendary German director for the natural world is quite apparent. Shot on 16mm by Kenny Suleimanagich, who brings a painterly touch in capturing the woodland landscape, Allen Sunshine is an affecting, understated look at picking up a life destroyed, and finding a connection with the people that can help put the pieces back together. – Jordan R. (full review)

Chronicles of a Wandering Saint (Tomás Gómez Bustillo)

Tomás Gómez Bustillo’s charming, intelligent Chronicles of a Wandering Saint is a natural follow-up to the two short films for which he is known: Soy Buenos Aires (a strange, picaresque rags-to-riches tale) and Museum of Fleeting Wonders (a collection of dramatized paranormal happenings). In Chronicles, as in the two short films, he is primarily concerned with spiritual, ethical, and religious contrasts; scenarios in which miracles are mixed with coincidences, faith with rationality, and boredom with inspiration. But that is where the comparisons end; for Chronicles is in every way a more serious, controlled, and moving work of art, which stands with the very best of contemporary Argentine cinema. – Oliver W. (full review)

The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed (Joanna Arnow)

A stellar portrait of modern malaise alongside the next pick, Joanna Arnow’s dryly funny The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed may not be deemed a debut feature for some, in light of her 56-minute i hate myself 🙂, but we’ll consider it as such. Rory O’Connor said in his review, “In The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed, Ann, a lugubrious New Yorker, sleepwalks through her daily life––colorless job, perennially disappointed parents––while maintaining a long-term sub/dom relationship with an older man. She visits her Jewish family, goes to yoga, and attempts some Internet dating. Invariably she winds up in her boyfriend’s lifeless brownstone. Executive-produced by Sean Baker, this is the feature debut of writer-director Joanna Arnow, a Brooklyn-based actor and filmmaker who made a name for herself as a wry observer of millennial sex lives and stasis with a couple of award-winning shorts: Bad at Dancing (2015) and Laying Out (2019). In Dancing, Arnow sat naked on the floor, casually asking for advice from a friend having sex right in front of her. The sense that everyone around you is getting their shit together (and maybe getting laid) is present again here; yet eight years hence, it arrives with the added humility of lived experience.”

Free Time (Ryan Martin Brown)

Free Time opens on an office meeting between Drew (Colin Burgess) and his boss. Drew is dissatisfied with his data-analysis position because it’s too much data entry and too little analysis. “The computers do all of the analysis for you now. It’s really just… data,” he laments. The meeting ends unexpectedly with Drew surprising himself (and his boss) by putting in his two-week notice. It’s a savvy cold open that clues us into Drew’s lack of self-awareness being a source of amusement in the narrative to follow. – Caleb H. (full review)

Good One (India Donaldson)

It’s been nearly two decades since Kelly Reichardt’s Old Joy showed how the wilderness can be an open canvas to explore the breaking points of male friendship and reckoning with a midlife crisis. While those emotional quandaries are evergreen, it’s appropriate timing to bring an entirely new element to this conceit. India Donaldson’s carefully observed, refreshingly patient, beautifully rendered debut feature Good One shifts the perspective, concerning a 17-year-old girl who embarks on a camping trip in the Catskills with her father and his best friend. Through an accumulation of minute details and uneasy glances, the drama becomes a portrait of increasingly crossed boundaries leading to an ultimate breaking point. – Jordan R. (full review)

Hundreds of Beavers (Mike Cheslik)

A film that more than delivers on the promise of its title, the plot of Hundreds of Beavers couldn’t be simpler: an applejack salesman attempts to outsmart, yes, hundreds of pesky critters to break into the fur-trapping game. That simplicity makes for a sandbox of endless imagination as we witness escalating hijinks that often find our lead on the losing side of the battle in hilariously agonizing ways. With an enduring love for silent-era slapstick comedy set against a homespun landscape that could be pulled from a Guy Maddin feature, it’s rather remarkable that the aesthetic only wears slightly thin. Rather, one comes away from the adventure with an invigorating sense that with enough creativity, the time-worn tricks of classic cinema can feel new again. – Jordan R.

In a Violent Nature (Chris Nash)

What new perspective can one bring to the horror genre? With his directorial debut, Chris Nash gives this question its resoundingly brutal, formally fascinating answer. Primarily following a murderer’s steps and slashes through his travels terrorizing those near a remote cabin, the wonderfully Béla Tarr-esque In a Violent Nature sticks to its meticulous conceit and delivers one of the most chilling horror movies I’ve seen in years. – Jordan R.

It’s What’s Inside (Greg Jardin)

There are few things better than when a good idea blossoms into a great movie. It’s What’s Inside, written and directed by Greg Jardin, achieves this rare feat. DIY in both aesthetic and narrative build, it suggests a labor of love. The premise is simple: a group of old college friends party at a big house the night before one of them gets married. Things seem sinister before anything bad has even happened. Or maybe the bad things already happened a long time ago. – Dan M. (full review)

Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell (Phạm Thiên Ân)

Early into Pham Thien An’s sprawling, stupefying Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell, there’s a shot that manifests Caravaggio inside a shack in rural Vietnam. Having traveled from Saigon to his home village to attend the funeral of his sister-in-law, Thien (Le Phong Vu) is visiting a local elder who sowed a shroud for the departed. The twenty-something wants to pay for the service; the old man doesn’t take money from neighbors. He does accept the company, though, and very generously spills a whole cascade of memories from the Vietnam War, laying bare an old bullet scar on his ribcage. And as Thien bends to graze the bruised skin under the warm, caliginous light, Pham frames the moment as one of reverential awe, an image modeled off of Caravaggio’s “The Incredulity of Saint Thomas.” It’s a beautiful shot in a film full of them. That it comes near the end of a particularly intricate 24-minute take is a testament to Pham’s mastery of craft; that this three-hour odyssey is only his first feature only adds to the wonder. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Janet Planet (Annie Baker)

About halfway through playwright Annie Baker’s self-assured and pitch-perfect directorial debut Janet Planet, 11-year-old Lacy (Zoe Ziegler) rolls over in bed and turns to her mother Janet (Julianne Nicholson) with an innocent prompt. “You know what’s funny?” she asks. “Every moment of my life is hell.” At such a gentle moment, in such a casual way, she delivers a melodramatic gut-punch. You can’t help choking out a laugh. – Jake K-S. (full review)

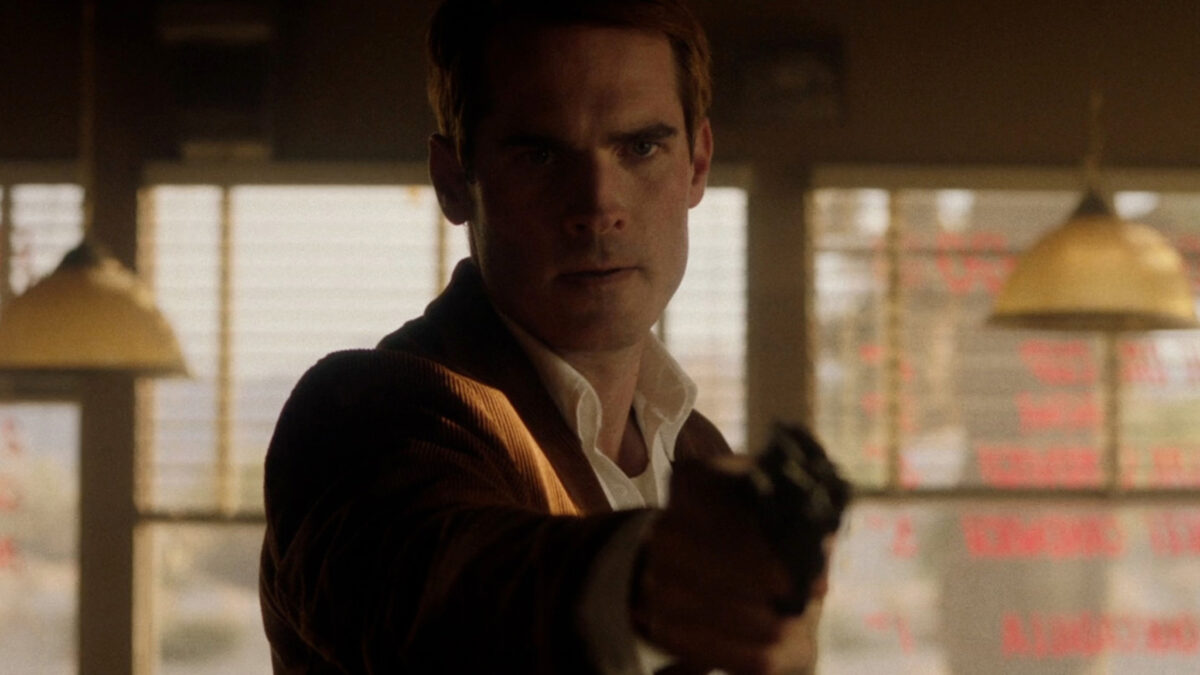

The Last Stop in Yuma County (Francis Galluppi)

After watching Francis Galluppi’s deliciously entertaining, bloody one-location noir thriller The Last Stop in Yuma County, it’s easy to see how Sam Raimi warmed to his pitch for a new Evil Dead movie and hired him for the next installment. Galluppi’s highly accomplished debut feature follows a traveling knife salesman (a pitch-perfect Jim Cummings) who gets stuck at an Arizona diner in the middle of nowhere when some nefarious criminals stop in. With dialogue and turns that would make even the Coens smile, this is an homage that has an identity all its own. – Jordan R.

Mountains (Monica Sorelle)

A low-key, poetic exploration of life’s ironies, Monica Sorelle’s feature debut Mountains frames the disappearance of Miami’s Little Haiti with a warm, compassionate gaze recalling the masters of social realism––akin to Roberto Rossellini with the touch of Ousmane Sembène’s lighter films. With a title drawn from a Haitian proverb “behind mountains there are mountains,” the film retains a light touch, somewhat more sad than mad as Little Haiti disappears in the city’s building boom. A modest dream home is unobtainable once the real estate vultures circle the neighborhood and Xavier Sr. (Atibon Nazaire), a demolition worker, plays a role in changing his neighborhood permanently, making way for young Whole Foods-shopping professionals to displace families and small businesses. – John F. (full review)

My First Film (Zia Anger)

Zia Anger’s name has been a kind of totem for underground film artistry, to whatever extent that seems to exist anymore. Her presentation-based My First Film made waves in recent years as the ultimate vision / confession of artistic failure and regret, making somewhat peculiar the existence of, let’s see what it’s called, My First Film, a feature debut-of-sorts that tells of her younger self’s failure to launch a filmmaking career. Or someone like her: the lead character is Vita, a shortsighted and temperamental young director failing to control cast, crew, ideas, or impulses; but present in the film is Zia, who reflects on this difficult time in the character’s (her?) life. Fear not any risk of complication: My First Film makes legible––dare I say universal?––thwarted dreams and personal embarrassment vis-a-vis the interplay of Anger’s actual work and Vita’s imagined endeavors. – Nick N. (full interview)

The People’s Joker (Vera Drew)

It’s a genuine miracle that The People’s Joker has managed to make it to screens unscathed, especially considering the legal battles which dogged the 2023 TIFF premiere could easily have left it trapped in the vault forever. Many of the rave reactions from that festival were written solely within the context of such lingering threat, with many critics doubling-up as armchair legal experts, not analyzing the qualities of Vera Drew’s film so much as they were assessing the likelihood of whether anybody else would ever see it. Now that this unauthorized take on the DC mythos is defiantly arriving on screens––albeit with a lengthy legal scrawl preceding the action itself––it’s immediately obvious that writing about it solely within the context of whether it constitutes a serious copyright violation is something of an insult. – Alistair R. (full review)

The Settlers (Felipe Gálvez)

The barbaric, bloody sins of the past come to define what entities govern certain land today, carried out by conquistadors and colonizers who hide behind righteous religious falsities to denigrate an indigenous population. With his directorial debut, a hauntingly conceived Chilean western The Settlers (Los Colonos), Felipe Gálvez localizes an origin story of this horror vis-a-vis the brutal genocide of the now-extinct Selk’nam people, who were native to the Patagonian region of southern Argentina and Chile. While spare early passages are narratively opaque and formally ornate to a distancing fault, the riveting second half––including a chilling reckoning with others occupying the desolate land and a well-executed structural gamble––brings profound expansion to this chilling story of atrocity. – Jordan R. (full review)

Honorable Mentions

Explore more of the best films of 2024.