Long before Hollywood director Steven Spielberg made the great white shark #1 on summertime ocean frolickers’ Most Wanted lists in the thriller “Jaws,” there was the megalodon — the biggest, baddest shark ever, replete with a movie marquee moniker.

Cue the suspenseful Jaws theme.

Weighing more than 60 tons — the equivalent of almost eight hulking circus elephants — and as long as a couple of freight cars, it had jaws wider than a lineup of SUVs.

Its cavernous mouth was lined with thick serrated triangular teeth, making the megalodon a living, breathing super-powerful buzz saw that could slice a giant whale in half and then swallow it whole.

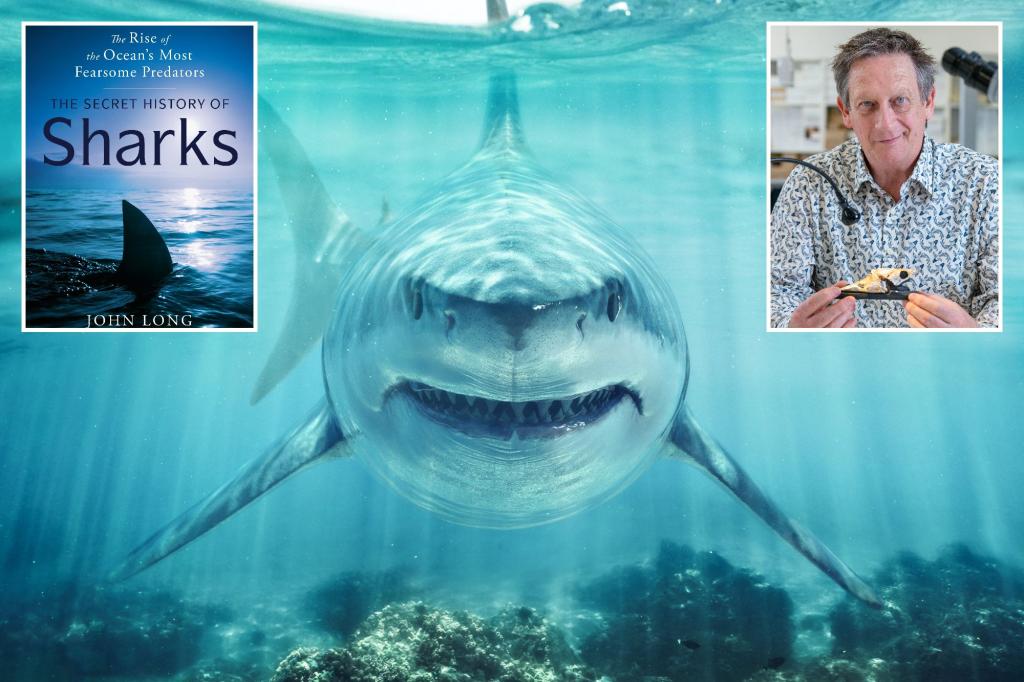

Now John Long, billed as the world’s leading paleontologist, introduces the megalodon, which he calls the “greatest super predator ever,” along with other killer sharks of the ocean deep in his fascinating new book, The Secret History of Sharks: The Rise of the Ocean’s Most Fearsome Predators (Ballantine), timed perfectly for this season’s chilling beach read.

Have no fear, beachgoers. Long, who has been performing “cutting edge” shark research for decades, points out in his highly readable, 467-page “untold story” of the shark world, that the megalodon suddenly vanished from the seas millions of years ago.

How and why, the author writes, is “one of the great mysteries” of shark paleontology.

“Today, sharks include some of the weirdest, wildest, and most spectacular creatures on our planet,” Long observes. He notes that the white shark is now “the ocean’s most feared predator”; that the hammerhead is the ocean’s “weirdest-shaped fish”; tiger sharks are the “voracious garbage eaters” of the seas. And then there is the “extraordinary” bullheads shark, which the author describes as “docile little fishes that are true living fossils, virtually unchanged from when dinosaurs ruled the earth 150 million years ago.”

The story of the shark, Long maintains, tells us about the very nature of survival of life on earth.

The strategic professor of paleontology at Australia’s Flinders University declares that without sharks, the earth’s marine resources “would diminish” and the oceans “would die.”

“Whatever nature has thrown at them, sharks, like the Terminator, just kept coming back.”

As part of his research, Long went on expeditions to all seven continents to search for never-before-discovered fossils of sharks, here on earth before the dinosaurs — some 465 million years ago.

“The missing piece of the puzzle,” he writes, “is where they came from, and how they survived for close to a half a billion years — escaping mass extinctions and major environmental crises — surviving catastrophic meteorite impacts, globally destructive gigantic volcanic eruptions, changing sea levels and temperatures, deadly fluctuations in global oxygen and CO₂ levels.”

What he discovered is that sharks have super-powers: They can smell small amounts of blood in the water from hundreds of yards away. They can detect the faint electrical fields of other living creatures — even buried under sand, and they can stun and or kill prey with a powerful electrical charge. No other aquatic land animals, he notes, have developed this power.

As an example, the author writes that it’s been claimed that sharks “can detect electric currents” as weak as one-billionth of a volt. And “if two AA batteries were connected under the sea, a shark could sense the charge from a thousand miles away.”

Then there’s the great white shark, always in the spotlight and nature at its most terrifying — as well as being the stuff of beachgoers’ nightmares.

Measuring as long as 20 feet and weighing over 4,000 pounds, the great white’s bite is more powerful than any land animal today, stalking their prey similar to human serial killers.

Their serrated, bladelike teeth — as long as 6 inches — are so strong they can rip into and kill whales and seals, and the great white can swallow a person whole.

But Professor Long looks beyond the pop culture-hyped killer instinct.

“These are not monsters, an illusion created in our media-frenzied minds by the grizzly and unnatural thought of sharks always wanting to attack and kill humans,” he writes.

“No, they are intelligent and sentient creatures that embody the apotheosis of evolution, fishes that after 450-million years have used natural selection to continuously improve their body design — and become one of the greatest predators on the planet.”

Still, Long believes that the future of the sharks is under “grave threat.”

He cites two examples of rare sharks – the 8-foot daggernose shark with its elongated, pointy snout, living mostly in South America, and the 9-foot Ganges shark, living in the Bay of Bangladesh, that are listed as “critically endangered” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Long believes that the rapid decline of the Ganges could be linked to over-fishing and severe pollution of its habitat.

His answers for shark survival?

“Unless countries talk to one another and agree to seriously regulate shark fishing, and to actively prosecute offenders,” declares Long, “it will simply not result in a realistic protection of any vulnerable species.”