“I can’t believe we’re here,” a friend said to me about halfway through this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato, which takes over the center of Bologna for nine glorious days every summer, before correcting himself: “It actually makes a lot of sense that we’re here, but I still can’t believe it.”

My friend was in awe not that we––a pair of New York cinephiles, both fairly well-traveled––managed to make it to beautiful Bologna, but that we had entered some kind of an Olympic village for cinephiles, each day filled with some of the most memorable moviegoing events of our lives and each night filled with hours of discussion about the day’s pleasures. At the festival, everyone’s first question is “how many years have you been coming?” and newcomers are warmly welcomed into the fray. The favored departure is not a “ciao” or a more formal “arrivederci” or even an English variant of “bye,” but the more cheerful “see you next year!”

Ballet Mécanique

I knew the hype that has grown louder with each passing year was earned on my first morning for a program of Dziga Vertov’s Kino-Pravda 18, Abel Gance’s Au Secours!, and Fernand Léger’s Ballet Mécanique (a documentary, fiction, and an avant-garde film, respectively, all from 1924) accompanied by percussionist Valentina Magaletti. Magaletti’s music was bold and modern, an approach to silent-cinema scoring that dates back at least as far as Giorgio Moroder’s work for Metropolis, but one that, in the wrong hands, can overwhelm the work, pulling it out of time and reversing the dynamic between sound and image, treating us to something more like a music video than a silent film. Needless to say, that was not the case. Magaletti’s interpretations––especially her drumming that accompanied Ballet Mecanique––supercharged them. Il Cinema Ritrovato is not a silent-film festival, but with the musical prowess on display here and elsewhere it surely is as good an occasion as any other for viewing them.

While the music of Il Cinema Ritrovato might make one wonder if the lifeblood of any festival truly is the movies, this one would not fall short by either metric. There was, at least at first, some grumbling on the ground about certain retrospectives this year. Anatole Litvak and Kozaburo Yoshimura are less-exciting names than last year’s Teisuke Kinugasa (A Page of Madness, Gate of Hell) and Rouben Mamoulian (Queen Christina, Blood and Sand) or the prior year’s Kenji Misumi (Lone Wolf and Cub, Zatoichi) and Hugo Fregonese (Apache Drums, Black Tuesday). In the case of Litvak, this wasn’t unfair––only Coeur de Lilas and its maximalist approach to sound (remarkable for 1932), crowded frames, and expensive sets stood out as a particularly authored achievement (although I missed L’Equipage, a festival favorite). With Coeur de Lilas, Litvak seems to be choreographing action for the camera and using sound to queue the audience to actions and events outside the frame; his other works shared little of that ingenuity, and his Hollywood films ranged from mediocre to enjoyable. As for Yoshimura, these concerns were quickly put to rest, as his seven features made for reliably strong pre-dinner viewing.

Osaka Monogatari

It’s always tempting, and frequently too easy, to compare every mid-20th-century Japanese melodramatist to Ozu and Mizoguchi––it’s even easier here, given that Yoshimura worked as an assistant director to Ozu and his Osaka Monogatari (1957) was originally meant for Mizoguchi––but such an approach suggests that lesser-known filmmakers are worthwhile primarily because of how they help us refine our understanding of the established masters. Yoshimura shares with many of his ‘50s peers an interest in women, but rather than holding them up as paragons of sacrifice or as metonyms for middle-class generational conflict, he positions them as agents fighting for survival, status, and recognition in a changing world. This is the case even in the wickedly satirical Osaka Monogatari, where the tyranny of a King Lear-esque figure is visited primarily on his children and their relationships. It was a constant even throughout the decade, even as his attitude toward the tension between westernization and Japanese traditionalism grew increasingly complex. Clothes of Deception (1951), the earliest film in the program, takes a more sociological and didactic approach, and while Sisters of Nishijin (1952), a loose adaptation of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchard, arguably flips the script ideologically, it still sometimes feels like the message is propelling the characters. The Naked Face of Night (1960), by contrast, uses a rivalry between two dancers to allegorically address the nation’s transition and is remarkable not merely for its ambivalence but in how deeply it examines the psychological effects of its scenario. Across the entire decade, though, Yoshimura adapts an unflashy but considered visual style, adeptly panning his camera for carefully staged deep space exteriors and occasionally making use of unexpected cuts––particularly jump cuts––as if asking us, quite literally, to consider other perspectives. His is one worth consideration on its own merits, not just in relation to his peers.

1950s Japanese melodramas are a safe bet, both because the films tend to be good and because it is relatively clear what you’re getting into before you watch. Only the former is true with the Cinema Libero program, whose better-known selections from the last couple of years include The Dupes, Ceddo, Eight Deadly Shots, and Black God, White Devil. It has a reputation for hosting some of the festival’s best films. This year was no exception, even as its selection––culled from the “global south”––sometimes leaves even the biggest cinephiles without antecedents. Because I know I’ll have chances in the near-future to see both, I missed two popular “best in fest” picks from the section in The Sealed Soil (Marva Nabili) and Camp de Thiaroye (Ousmane Sembène, Thierno Faty Sow); still, Lino Brocka’s Bona and Assia Djebar’s La Nouba des femmes du Mont Chenoua were more than serviceable as personal highlights.

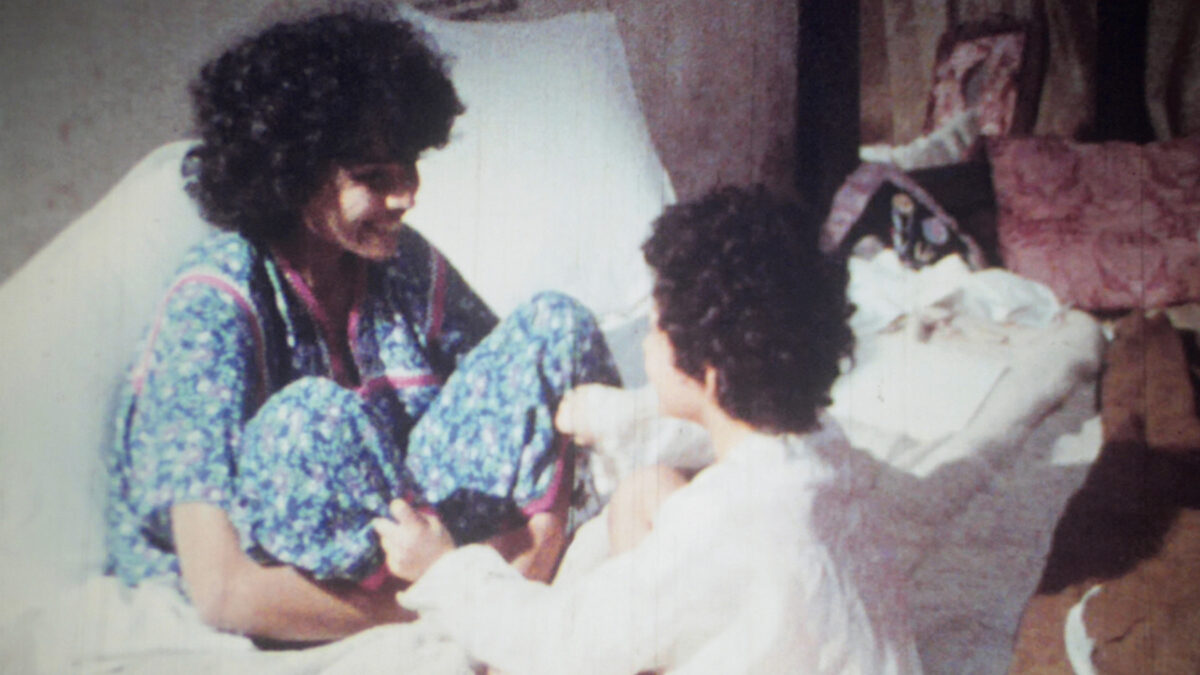

Bona

Bona (1980) fits neatly into the space carved out by Brocka’s Manila in the Claws of Light and Insiang in that it combines elements of neorealism––location shooting and a narrative about the impoverished and downtrodden––with the high melodrama of “women’s pictures.” In this one, the eponymous character, played by Philippine cinema superstar Nora Aunor (who held the rights to the film before they were acquired by Carlotta Films and Kani Releasing last year) sleeps with Gardo, an attractive bit player in the movies, gets kicked out of her home for it, and then finds herself kicked around all over again once she takes up residence with him. Brocka’s depth of field and street scenes ensure that all the dramatic action feels like but one story among many; indeed, much of the film involves characters seeking advice or having their fortunes intertwined with that of their neighbors. As a result, what plays out is not merely domestic drama, but something with larger allegorical implications. Gardo and Bona represent not just themselves, nor even men and women generally, but the Marcos dictatorship and the people of the Philippines. Given this nascent political content, Brocka’s prolificacy is something of a miracle, and it’s been a joy to watch, over the last 15-or-so years, his films begin to recirculate at a steady (albeit slow) clip.

La Nouba des femmes du Mont Chenoua (1979), the best film I watched at the festival, was made in Algeria in the spring of 1976 (though first screened three years later), explores the post-colonial condition of Algeria and the social place of women, and it borrows its structure from a nouba, an Arabic musical-poetic tradition with origins in Moorish Spain, with music composed by Béla Bartók. Already, then, the film is avoiding simplistic ideas of nationalism and belonging––it is made in and about an independent Algeria, but structured after a Spanish-influenced Arabic musical form, with music composed by a European who studied in Algeria. To complicate matters further, Djebar has stated that her two biggest cinematic influences were Bergman and Pasolini––the latter perhaps detectable in Djebar’s interest in those surviving on the outskirts of society, but neither especially detectable.

La Nouba des femmes du Mont Chenoua

The film loosely follows an intellectual, even bourgeois, woman who returns to post-colonial Algeria some 15 years after the country achieves independence as she recounts her life, uncovers her history, and observes and befriends rural Algerians, especially women. The history she uncovers is not strictly personal nor national, but feminist––Djebar has stated that she first recorded the stories of the women heard in the film, then came up with images to match. Like the best politically radical cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, then, it takes seriously the idea that radical ideas require radical forms to express. La Nouba is full of apparently detached landscape shots that convey both the alienation of Antonioni and the reverence and longing for homeland and belonging in Taiwanese New Wave filmmakers, but the closest analogue, appropriately, is Tariq Teguia’s equally overlooked Inland, another Algerian film that is unafraid to shift from the dramatic to the documentary to the essayistic in the space of a cut. If anything can justify the absurdity (not to mention the costs) of flying across the ocean and spending more than a week watching a half-dozen movies a day, it’s the possibility of encountering a film like La Nouba, which reminds me that the possibilities of cinema are limitless and that there are always more great films to discover, and sharing it with whoever will listen.

If I could hardly believe I was there even at the festival’s halfway point, it didn’t make it any easier to believe it was over just a few days later. So strong is the programming at Il Cinema Ritrovato that I could have filled this piece with an entirely different set of films––Louis Feuillade’s Judex, Mohammad Malas’ Al-Leil, Boris Barnet’s The Wrestler and the Clown, the early films of Sergei Parajanov, and the rediscovered silent masterpiece Count Cruel––and raved all the same. And while there were plenty of films that friends and colleagues loved that I could not catch, my only regret is that it’s over––at least until next year.