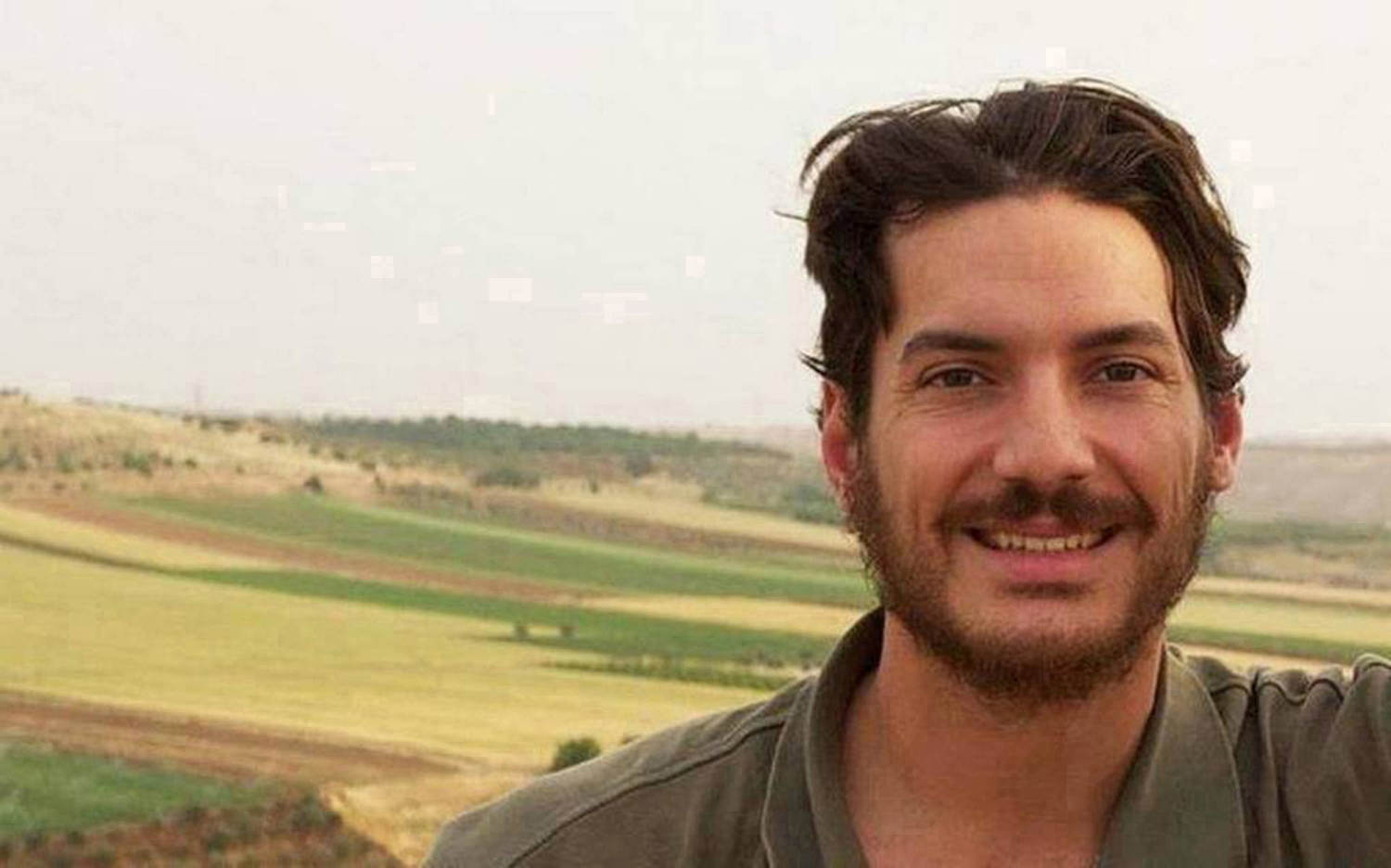

The campaign to bring Austin Tice home started long ago, in August 2012. Soon after, his family, the government, employers and a small but determined group of skilled supporters were deeply involved. None of them, least of all Austin, could have known this ordeal would last more than 12 years.

The Tice family made a decision in 2012 that Austin’s lead advocates would be his mom and dad. Debra and Marc Tice wanted their children to live their lives and not be defined by what had happened to their elder brother. This has proven to be a good strategy. The Tice siblings are an impressive lot. They have achieved much in their lives and exhibit admirable confidence, strength and a surprisingly robust sense of humor. The parents have done an amazing job advocating for their son’s release but are starting to show the emotional damage that comes from an unprecedented 12-year campaign.

This month all 17 members of the extended Tice family came to Washington in an effort to push for Austin’s release. It was a formidable show of force.

This month all 17 members of the extended Tice family came to Washington in an effort to push for Austin’s release. It was a formidable show of force.

With President Joe Biden on his way out of office amid the growing turmoil in Syria, there was a small window of opportunity. Transitions between administrations often become quiet periods of several months for hostage cases. But, Austin may not have months to spare.

In the summer, when Biden announced he would end his presidential campaign, Debra Tice looked at calendars and planned a date in December when the family could all gather in Washington, D.C. — from Australia, London, Texas and Tacoma, Washington. With the 2024 election settled we hoped we could use the time to make sure Austin’s recovery was on Biden’s list of legacy projects. And why shouldn’t it be? No journalist has ever been held as long. Austin is not only a Polk Award winning journalist, but a Marine veteran of Afghanistan and Iraq, law student, Eagle Scout and Texan. Syria might as well be holding America itself hostage.

Biden has a genius for pulling together complex diplomatic deals like the Russia prisoner swap in August. He would need all that skill and experience to succeed in bringing Austin home.

As Dec. 6 approached time itself felt like it was accelerating. Shortly after the Tices arrived in the Capitol, Damascus fell. The careful plan was in the wind. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, one of the biggest obstacles to Austin’s freedom, fled to Russia. Cell doors were opening. The hunt for Austin was on.

None of this seemed possible when I had coffee with Debra Tice in the summer. One of the most challenging aspects of advocating for detained journalists is that change can overtake planning. Schedules changed. Plane flights were canceled. There were Tices on every TV outlet in D.C. They were pounding their talking points: The U.S. must ask Russia to get Assad to tell where Austin is; the U.S. must ask Israel to stop bombing Syrian prison locations: the U.S. must engage with the new emerging government of Syria; our brother is alive; we have confirmed sources; we miss him; we want him home.

This is how it is for the family. They must be the messengers. But in a way we all lose something when a journalist is jailed. The U.S. system depends on citizens having information about the world. When a journalist is taken, that information becomes harder to find. Hostage takers throw sand in the gears of democracy.

This is how it is for the family. They must be the messengers. But in a way we all lose something when a journalist is jailed.

The jailing of journalists like Austin Tice, Evan Gershkovich and Alsu Kurmasheva affects our world in other, unexpected ways as well. Superpowers like the United States have long survived on their ability to project power. We do not have to fight for everything we want. We just need to show we were ready or able to fight. The ability to project power settles many disputes and saves lives. It gets things done. But our inability to bring journalists like Austin home undermines that perception of power, too.

While little can be done to deter hostage taking, there are a few important proposals being considered. U.S. courts are starting to award large judgments to families who sue the countries that take hostages, but there is no mechanism for families to collect. Without such a mechanism, these judgments do not act as deterrents. The U.S. can and should do more here to identify and freeze the assets of those culpable. Experts believe this would greatly reduce hostage taking. Doing nothing is not a policy.

The new Press Freedom Center at the National Press Club, where I currently serve as director, has proposed that the government should revise its policy on hostages and immediately give a presumptive declaration of wrongful detention when journalists are targeted. Recently, Gershhovich was held for 13 days before the U.S. government declared him wrongfully detained. Kurmasheva, another U.S. journalist, was jailed in Russia for 250 days and only upon release was declared officially wrongfully detained. In other words, there are plenty of things the U.S. government can do to better protect American reporters working overseas and plenty of reasons for them to do so.

But first, lets bring Austin Tice home.