The Big Picture

- Both

Longlegs

and

Cure

showcase chilling killers who find joy in corrupting and destroying normal families. - The distinct motives of

Cure

‘s antagonist suggest that human nature holds a dark, murderous capability waiting to be unleashed. -

Cure

delves into the terrifying idea that hypnotism unlocks an individual’s true self, filled with murderous resentment and darkness.

Osgood Perkins‘ Longlegs is in theaters, and it’s a terrifying, moody exhibition of some of the darkest events cinema has to offer. The film follows newly minted FBI agent Lee Harker (Maika Monroe) set on the trail of a serial killer with a vicious and mysterious modus operandi. In one particular region of Oregon (going back decades), there’s always a seemingly healthy family, with a seemingly loving father, who violently murders his entire family (using a weapon he owns) before killing himself. There are typically satanic markings on the wall, but there’s no real evidence or connection between the families other than a card at each crime scene, signed with “Longlegs.” Lee Harker has to use her psychic (well, half-psychic) abilities and obsessive tendencies to get to the bottom of this terrible, community-destroying set of serial killings as it circles ever closer to the ones she loves. It’s a terrible spree of killings centered around an even more terrible killer who gets unwitting strangers to do his evil bidding, all with a well-meaning detective (albeit touched by evil) on the chase.

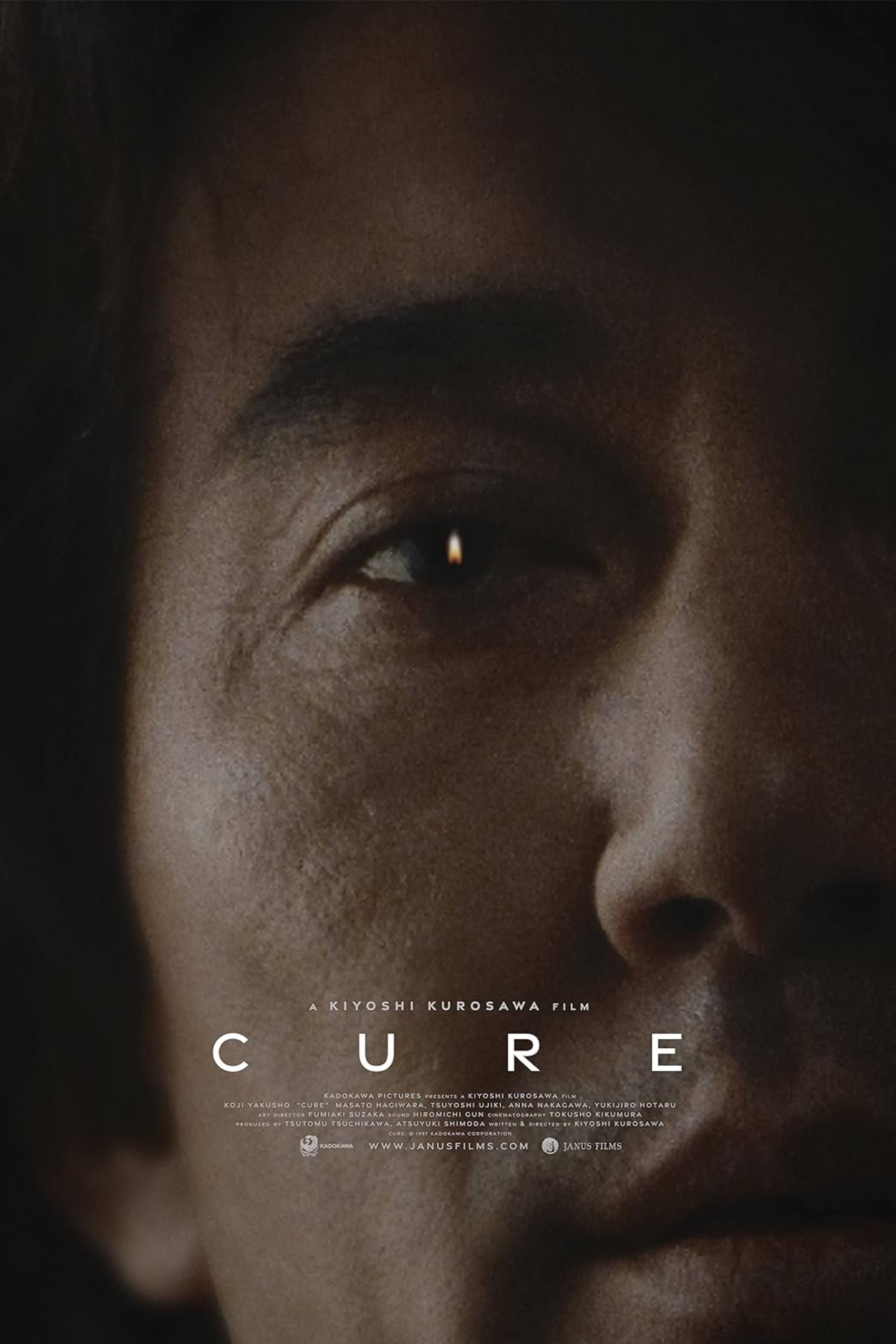

Japanese master filmmaker Kiyoshi Kurosawa is exceptional at finding meditative bleakness in everyday locales and the odd corners of humanity, like in his ode to computer isolation, Pulse, or the recent short, Chime, where a simple cooking instructor’s life is turned upside down when he starts to hear a strange sound. Kurosawa’s 1997 psychological horror neo-noir outing Cure has a simple premise that Longlegs fans might find familiar. The film follows Tokyo detective Kenichi Takabe (Koji Yakusho) as he investigates a set of violent serial killings, much like the ones in Longlegs, with no apparent motive or connection between the killers save for a particularly violent pattern. As the investigation escalates, Kenichi discovers a common thread between them, a master manipulator named Kunio Mamiya (Masato Hagiwara) with a disaffectingly empty countenance. For anyone under Longlegs’ bleak spell, Cure should be the next entry on their watchlist, but watch out: as disturbing as Longlegs is, Cure has far more unsettling implications.

Like ‘Longlegs,’ Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s ‘Cure’ Follows a Deranged Serial Killer

In Cure, Japan is plagued by a series of killings that defy easy investigation. In each instance, someone is brutally killed in a similar, gruesome death ending with an “X” shape carved into their neck and upper torso. Each time, the seemingly disconnected murderers casually and suddenly perform the vicious kill, then afterward describe the act while recoiling in horror: it felt natural at the time, but they have no idea why they did it. The only link that emerges is a man named Mamiya, a frustratingly mysterious suspect who feigns amnesia but is actually a brilliant psychopath with an evil plan and a grim outlook on humanity. As Kenichi gets closer to Mamiya’s secret, the killings close in on him as Mamiya seeks to get inside his head and unlock his inner darkness. The chilling film’s broad strokes bear a striking resemblance to Longlegs, each following a violent slew of disconnected killers fitting a strange pattern whose only connection is a mysterious man at the center.

7:44

Related

Oz Perkins Explains the End of ‘Longlegs,’ and It’s Bleak

Perkins also discusses how he came up with the title for the film.

Longlegs‘ murderous mastermind is a sincere Satanist working in service to “Mr. Downstairs,” taking pleasure in corrupting and devastating ordinarily normal families over decades. Cure‘s mysterious Mamiya is similarly devoted to spreading chaos and suffering on behalf of someone else’s historical campaign. Kenichi discovers that Mamiya was obsessed with early hypnotism, then called Mesmerism (after controversial German doctor Franz Mesmer, who the film asserts was accused of alchemy). It’s revealed to the audience that in an earlier era in Japan, “Mesmerism” was called “soul conjuring” and needed to be practiced in secret ceremonies. These ceremonies were pioneered by a mysterious man in the past (Cure never shows his full face) and had some curious side effects. A woman “treated” for hysteria using the practice, which involved the making of an “X” motion with the Mesmerist’s hand, later killed her son in a way similar to the current crime spree. It’s this mysterious early practitioner’s Mesmerism (possibly tied to alchemy or other forces) that Mamiya is obsessed with and hopes to give new life to, in his own way, serving a master by reproducing these ceremonies.

‘Cure’ Is More Terrifying Than ‘Longlegs’ For This Reason

What’s most frightening about both Longlegs and Cure isn’t necessarily the violent deaths or the eerie figure at their center; it’s the worldview of each antagonist. Both find joy in the destruction of normal humanity and community, but what makes Cure even more frightening is the distinct implications of the antagonist’s motives. For Longlegs, the titular villain clearly delights in corruption. There’s a reason why he goes after (at least seemingly) loving families, and why the murders hinge around children’s birthdays, days that should be innocent and celebratory. He gives the family a gift, and that gift is their doom on a day when gifts should be tokens of love. Perhaps he delights most in his impact on Lee Harker and her mother, happily taunting Lee about that connection in his FBI interrogation.

What’s interesting, however, is that as much as Longlegs centers around the corruption of families, it can be interpreted in a way that easily suggests it’s Longlegs’ Satanic power directly causing the terror. The implication that one’s own will can be overridden by the Devil is terrifying, certainly, but there’s really nothing to fear: just keep the Devil outside and the danger is kept at bay. In Cure, Mamiya also uses mysterious, possibly supernaturally-influenced means to control the killers he infects. It’s a specific set of practices that had at one time been considered supernatural, and it is left mysterious. Behind Mamiya’s seeming blank-slate nature, however, is a unique interpretation of how his actions impact human nature and will.

An early conversation between Kenichi and his coworker, psychologist Shin Sakuma (Tsuyoshi Ujiki), suggests that hypnotism can’t make someone do something they wouldn’t otherwise do. While this specific Mesmerism practice may be able to do something traditional hypnotism can’t, Mamiya clearly believes he’s merely unlocking darkness already present in his victims. First, the use of repetitive, elemental devices like flame or water is designed to make someone “empty,” just as he tells Kenichi during an interrogation interrupted by a ceiling leak that “the water will make you calm, it will make you happy, empty… you’ll be born again, just like me.” Once emptied, Mamiya focuses the victim on targets for their resentment, anger, or hatred, sparking their drive to kill.

After trying to affect Detective Kenichi throughout the film, when Mamiya is confronted by the detective in his lair in the film’s finale, Mamiya tells him “Anyone who wants to meet his true self will come here,” to the center of Mamiya’s dark plan. To Mamiya, his hypnotism is merely unlocking the victim’s true self, a shell that contains little beyond murderous resentment that the hypnotism (supernatural or not) merely unlocks. Where Longlegs makes victims empty vessels for Satan’s will — utterly terrifying in its own right — Cure‘s Mamiya is proposing that the core of our being is a murderous capability, waiting to vent our frustrations through bloody murder. It’s one of the bleakest stances on human nature in film history, and the real source of the film’s terrors.

Cure is available to stream on The Criterion Channel.

Watch on Criterion