The running joke around the Los Angeles Police Department for the last few years was that if you wanted a promotion, you had better learn to ride a bike.

Former Chief Michel Moore was an avid cyclist, and career-minded officers jockeyed to get into his riding group in hopes of currying favor before the next promotional list came out.

Police officers on bicycles make there way to the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial in Washington, D.C., on May 12, 2015. The officers rode for three days from Portsmouth, Va., to Washington as part of the Police Unity Tour to honor fallen police officers.

(Brett Carlsen / Associated Press)

Moving up the ladder is often about who you know. But with the city searching for a new chief after Moore’s departure this year, a growing number of department officials are privately lobbying for an outsider who can breathe new life into the organization.

A police executive who didn’t come up through the LAPD is more likely to challenge the favoritism — or the perception of it — that has been a way of life on the force for decades, according to interviews with more than a dozen past and current LAPD officials and others familiar with the department’s inner workings. Some current officials requested anonymity in order to be able to speak frankly without fear of career repercussions.

At the same time, they say, navigating the department’s insular, we-know-best culture might prove difficult for an outsider. Mayor Karen Bass will hire the next chief, choosing from nominees provided by the Police Commission and an outside hiring firm. The deadline to apply closed over the weekend, and an initial round of candidate interviews was set to start Monday. A final decision is not expected until this fall.

Interim LAPD Chief Dominic Choi shakes hands with Mayor Karen Bass after being named to the position at City Hall on Feb. 7, 2024 in Los Angeles.

(Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times)

Sharon Papa, a former deputy chief who joined the LAPD in 1997 as an outsider when the department absorbed the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s police force, said the choice of the next chief will indicate whether Bass approves of how the LAPD has been run in recent years: “Is she looking for someone to come in and shake things up from top to bottom?”

Former Houston and Miami Police Chief Art Acevedo is considered as a serious contender — a sign, some observers say, of the relative inexperience of some internal candidates. High-profile former police leaders from New York City and Seattle are also rumored to have applied, although the list of candidates is not public. The commission has also declined to release the number of candidates who applied.

Asked recently whether an outsider could successfully navigate the department’s culture, interim Chief Dominic Choi was noncommittal, but said he’s confident Bass would pick the “most qualified candidate” regardless of where they started their careers.

Choi said the department is “looking to have an internal assessment done of what our officers and command staff perceive as challenges in this organization.”

Dominic Choi speaks after his appointment.

(Gina Ferazzi/Los Angeles Times)

The feedback will be passed on to the new chief to “give them a little bit of a road map to start off on,” Choi said.

Choi rose through the senior ranks under Moore, who earned a reputation as policy wonk who could rattle off the minute details of running the nation’s third-largest police force — and expected the same of his subordinates.

But multiple sources said Moore, who still works for the department as a $20,000-a-month consultant, became a micromanager as his first term wound down, insisting on approving even minor decisions. Some believed that Moore punished those who challenged him directly, which created a groupthink mentality among the command staff that made them unable or reluctant to second-guess the “LAPD way.”

Moore did not respond to a request for comment.

Although the former chief no longer attends command staff meetings, attendees say his presence is felt in the buzzwords that became popular during his tenure. Recently, some senior staff members began circulating a tongue-in-cheek list of the 50 most commonly overheard expressions, including “push through,” “answer the bell” and “multi-prong approach.”

For decades, the LAPD hired leaders from in-house. Chiefs would stay in office until they retired or decided to step down, passing the reins to the next leader, who had risen through the ranks. The belief was that by working in a city as vast and diverse as L.A., officers are getting a first-class education in policing; running a busy division such as 77th Street or Newton was seen as akin to leading a small-town police department.

But success in such posts was not the only path to top jobs. At the LAPD, careers have been made and lost by connections.

Moore’s cycling club was not unprecedented. Former Chief Daryl Gates was an avid jogger, while Ed Davis, who led the department for much of the 1970s, was a golfer, which led their proteges to pound the pavement or hit the links.

Two of the biggest scandals in the department’s history opened the door to the appointment of chiefs who didn’t start their careers with the LAPD: Willie L. Williams and William J. Bratton.

Williams’ rocky tenure, in particular, serves as a cautionary tale.

The city’s first Black chief — and its first outside leader in more than four decades — Williams was credited with steadying the LAPD in the wake of the uprising sparked by the acquittal of four officers in the beating of Rodney King.

But department veterans say the former Philadelphia police commissioner was never fully accepted in L.A., in large part because of a long list of professional shortcomings and missteps, which included lying about paid junkets to Las Vegas, making questionable personnel moves and being slow to respond after the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

But in a department that long prided itself for its crisp, snappy appearance, he was also ridiculed inside roll calls across the city for his weight and how he looked in his uniform. Others were turned off by the fact that he didn’t carry a service revolver after failing to complete the requirements for California peace officers and his insistence on referring to senior officials as “white shirts.”

He lasted only five years, with the Police Commission citing his ineffective leadership in denying him a second term. Williams died in 2016 after a long battle with pancreatic cancer.

Papa, the former deputy chief, said the department is less closed off than it used to be but any outside candidates should learn from the experience of Williams, who “had no support network inside the department and he came in with no one to guide him.”

As a result, she said, the LAPD culture “spit him out.”

When Bratton took over the department in 2002 in the wake of the Rampart scandal, in which officers were caught taking drug money and planting evidence, he sought to insulate himself from the cliquish and hypercompetitive culture by promoting other department newcomers to key positions.

Bratton “knew he needed people he trusted who were objective,” Papa said of the former top cop in New York City and Boston.

Bratton also tried to breach the department’s insularity by pushing senior staff to become more involved in major police associations such as the International Assn. of Chiefs of Police to expose them to new ideas and challenge the sense of LAPD exceptionalism that suggests the department sets the tone for American policing.

“That cross-pollination is important,” Papa said.

After Williams, the department’s next leader came from within. Bernard Parks, chief from 1997 to 2002, had a reputation as a tough disciplinarian, which frequently put him at odds with the police union.

But Parks also faced criticism for limiting the scope of the Rampart investigation, which longtime civil rights attorney Greg Yates said was typical of an old-school LAPD mind-set that resisted outside oversight.

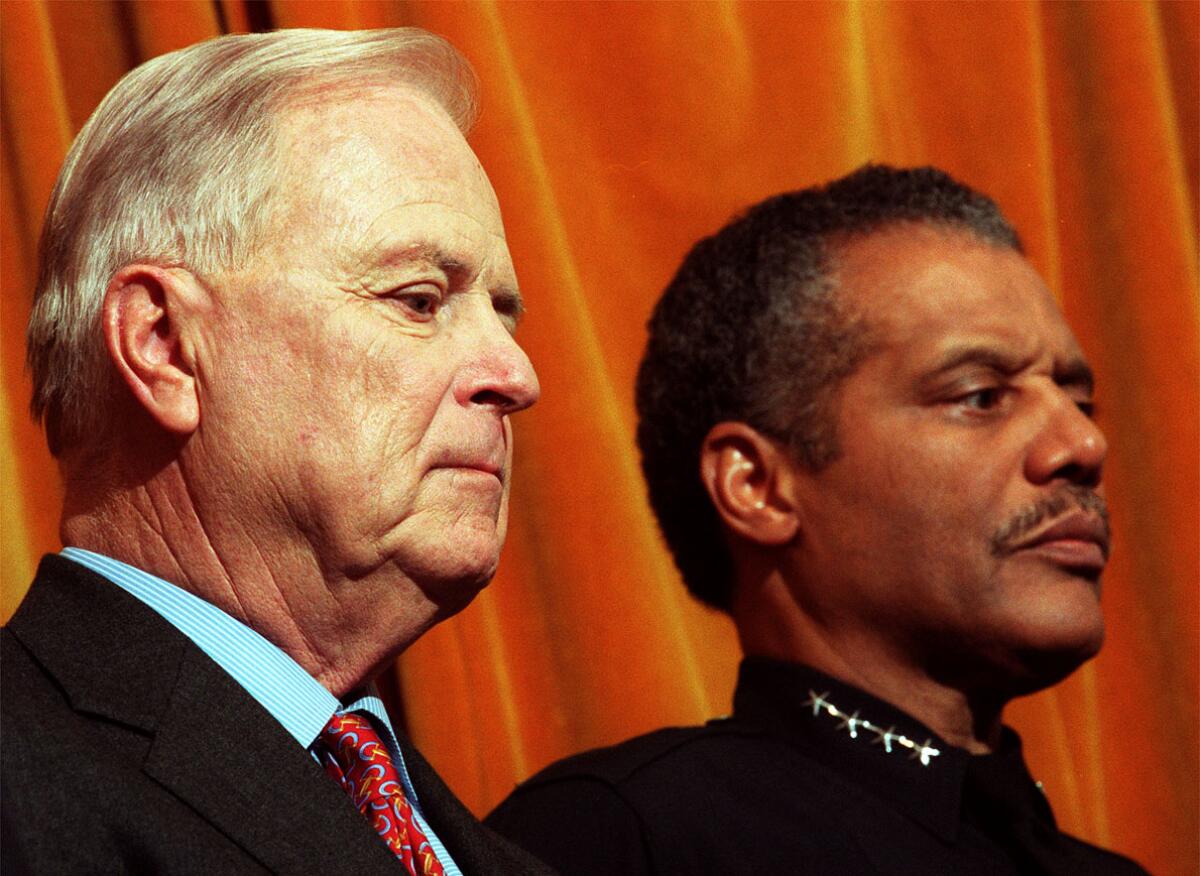

Then-Mayor Richard Riordan and then-Chief Bernard Parks at a news conference where they announced that the FBI would be assisting in the Rampart scandal.

(Rick Meyer/Los Angeles Times)

“He would have been like, you know, the guy that [spoke out about misconduct] was the rat, that was the snitch,” said Yates, who handled many Rampart-related abuse cases.

In a recent interview with The Times, Parks scoffed at the idea that he didn’t take the scandal — or more accountability in general — seriously, saying he fired 140 cops during his tenure and proactively enacted reforms well before they were suggested by federal officials.

“How could you be doing all of those things and still be upholding to the negative parts of LAPD culture?” he said.

Hiring from outside the LAPD does not guarantee innovation, Parks said. He argued that despite Bratton’s reputation as a progressive reformer, the former NYPD commissioner was also responsible for importing his brand of stop-and-frisk policies that critics say were used to justify the over-policing of Black and Latino communities.

The scandals that have plagued the department during Moore’s tenure are perhaps the strongest case for hiring an outsider, said attorney Greg Smith, who has represented dozens of officers — and a growing number of senior officials — in lawsuits against the department for retaliation and harassment.

The next chief will be “stepping into a department that’s full of cronyism,” Smith said. “You need an outsider who’s going to come in and is not beholden to anybody to break all this up.”

Art Lopez had left the LAPD as a deputy chief to take the top job with the Oxnard Police Department and was considered an outsider when he was named a finalist for the post that eventually went to Bratton.

Lopez said his years away from L.A. were instructive, showing him how far the LAPD was ahead of other departments, but also how Oxnard was “years ahead” when it came to community policing.

“It wasn’t just the fact that they had programs; it was a philosophy on the part of the police officers. They truly were part of the community, and that’s what we really needed in the Los Angeles Police Department,” he said.

Every big-city agency has its own set of idiosyncrasies, but the cultural gap between agencies isn’t as big as some would believe, according to retired Philadelphia and Washington, D.C., Police Chief Charles Ramsey, who spent the first 30 years of his career working in Chicago.

Ramsey said he tried various tactics to get his officers to buy into his plans and found one message that worked: “It doesn’t matter if the person is loyal to me personally, be loyal to the organization, be loyal to the profession, and if you can do that, we can work together — we don’t have to socialize.”

Chuck Wexler, director of the Police Executive Research Forum, a think tank that helped the city hire Bratton, said the department can be receptive to an outsider with the right approach. He said Bratton endeared himself to officers by enrolling in the department’s training academy, having a firm grasp of where the LAPD came from historically and knowing what traditions mattered to officers.

“In order to change the culture, you need to understand the culture, and there are certain aspects of the LAPD culture that Bratton did not change,” he said.

“You cannot change a department if you alienate the whole department,” he added. “People come in thinking, ‘Oh, I’m gonna come in change this and that’ — that’s not how it works. That’s a rookie mistake.”