A coating 100 times thinner than a human hair could be “ink-jetted” onto your backpack, cell phone or car roof to harness the sun’s energy, new research shows, in a development that could reduce the world’s need for solar farms that take up huge swaths of land.

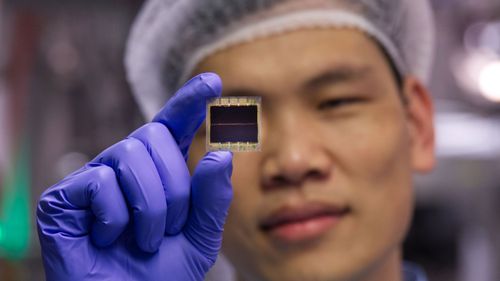

Scientists from Oxford University’s physics department have developed a micro-thin, light-absorbing material flexible enough to apply to the surface of almost any building or object — with the potential to generate up to nearly twice the amount of energy of current solar panels.

The technology comes at a critical time for the solar power boom as human-caused climate change is rapidly warming the planet, forcing the world to accelerate its transition to clean energy.

Here’s how it works: The solar coating is made of materials called perovskites, which are more efficient at absorbing the sun’s energy than the silicon-based panels widely used today.

That because its light-absorbing layers can capture a wider range of light from the sun’s spectrum than traditional panels. And more light means more energy.

The Oxford scientists aren’t the only ones who have produced this type of coating, but theirs is notably efficient, capturing around 27 per cent of the energy in sunlight.

Today’s solar panels that use silicon cells, by comparison, typically covert up to 22 per cent of sunlight into power.

The researchers believe that over time, perovskites will be able to deliver efficiency exceeding 45 per cent, pointing to the increase in yield they were able to achieve during just five years of experimenting, from six per cent to 27 per cent.

“This is important because it promises more solar power without the need for silicon-based panels or specially-built solar farms,” Junke Wang, one of the Oxford scientists said.

“We can envisage perovskite coatings being applied to broader types of surface to generate cheap solar power, such as the roof of cars and buildings and even the backs of mobile phones.”

At just over one micron thick, the coating is 150 times thinner than a silicon wafter used in today’s solar panels.

And unlike existing silicon panels, the perovskites can be applied to almost any surface, including plastics and paper, using tools like an inkjet printer.

Globally, solar panel installations have skyrocketed, growing by 80 per cent in 2023 compared to 2022, according to Wood Mackenzie, a company specialising in data and analytics for the clean energy transition.

Solar was the fastest-growing source of electricity in 2023 for the 19th consecutive year, according to climate think tank Ember’s 2024 Global Electricity Review.

A major driver of this boom is the falling cost of solar, which has now become cheaper to produce than any other form of energy, including fossil fuels.

Another important factor fueling solar’s rise is its growing efficiency in converting the sun’s energy.

But ground-based solar farms take up a lot of land, and they are often at the heart of conflict between the agricultural industry and the governments and companies behind the renewable installations.

Oxford’s researchers say their technology could offer a solution to that problem, while driving down energy costs.

But Wang noted that the research group is not advocating for the end of solar farms.

“I wouldn’t say we want to eliminate solar farms because obviously we need lots of areas or surfaces to generate sufficient amount of solar energy,” he told CNN.

A persistent problem with perovskites, however, is stability, which has prevented its developers from commercialising the technology.

Some coatings in lab settings have dissolved or broken down over short periods of time, so are regarded as less durable than today’s solar panels.

Scientists are working toward improving its lifespan.

Henry Snaith, the Oxford team’s lead researcher, said their work has strong commercial potential and could be used in industries like construction and car manufacturing.

“The latest innovations in solar materials and techniques demonstrated in our labs could become a platform for a new industry, manufacturing materials to generate solar energy more sustainably and cheaply by using existing buildings, vehicles, and objects,” he said.

Snaith is also the head of Oxford PV, a company spun out of Oxford University Physics, who has recently started large-scale manufacturing of perovskite solar panels at its factory in Germany.