As a housing activist, Maria Lopez spent years working to close what she saw as a significant, if little known, loophole in eviction law.

Working with the Long Beach Tenants Union, Lopez organized dozens of renters facing “substantial remodel” evictions across her hometown, speaking at City Council meetings and leading protests to draw attention to the rule, which allows landlords to evict tenants if they plan significant renovations to their properties.

From Lopez’s perspective, the rules allowed landlords looking to raise rents to evict tenants for minor upgrades or remodels that never happened once the tenant was gone. Her work helped push Long Beach to impose regulations on such evictions and influenced a recent change in state law aimed at tightening restrictions on them.

Then late last year, not long after a new owner bought the duplex Lopez has lived in since she was 6 years old, she was handed an eviction notice of her own. The reason? Substantial remodel.

“My heart just sank,” Lopez, 32, said of the moment when she got the notice.

Tenant advocates have raised concerns about substantial remodel evictions since the 2019 Tenant Protection Act was approved in California to limit rent increases and offer renters some protections against being evicted without cause. Under that law, one permissible reason for eviction is if an owner is planning a “substantial remodel” of a unit.

“We were getting stories from advocates telling us ‘We got a bunch of tenants that got these substantial remodel notices and we learned there was never any work done or it was something like new cabinets in the kitchen.’ And there wasn’t any recourse for those tenants,” said Lorraine López, senior attorney at Western Center on Law & Poverty.

Maria Lopez began to get involved in fighting substantial remodel evictions when she started hearing about a number of evictions soon after the 2019 law was approved. She met tenants at apartment complexes across Long Beach who had been served with notices to evict and began working with them to try and stop the evictions.

Maria Lopez looks on while outside near her garden in Long Beach this month.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

The issue gained urgency during the pandemic, when advocates say, it appeared that some landlords were using the rules to get around eviction moratoriums.

At a Long Beach City Council meeting in 2021, Lopez pleaded with officials to adjust the law.

“Many tenants are being kicked out for minor cosmetic repairs like cabinet or tile replacement, not substantial remodels,” Lopez was quoted as saying in the Signal Tribune. “Please, I beg you, I implore you, keep our families housed.”

That year, in response to advocates, the city temporarily banned substantial remodel evictions. Later, it moved to begin tracking remodel-based evictions, increase relocation assistance for displaced renters and allow for penalties for landlords who violate the law. This year, the state also tightened rules, including making it clear that tenants cannot be evicted for minor cosmetic repairs.

Lopez was proud of the accomplishment but felt remodel-based evictions should have been banned outright.

Last August, she learned that Dr. Femi Akinnagbe, a family medicine doctor, had bought the property she has lived in for nearly three decades.

Lopez moved in as a child with her family and stayed after her mother, father and siblings left. In downtown Long Beach, she was paying $675 a month until the new owners increased it to $734 soon after buying the property. The one-bedroom unit is adorned with posters and mementos from her work as a housing advocate — there’s a painting a local artist made of her, cradling a small home in her hands, a poster that says “End Eviction Loopholes Now” and numerous books on housing and evictions.

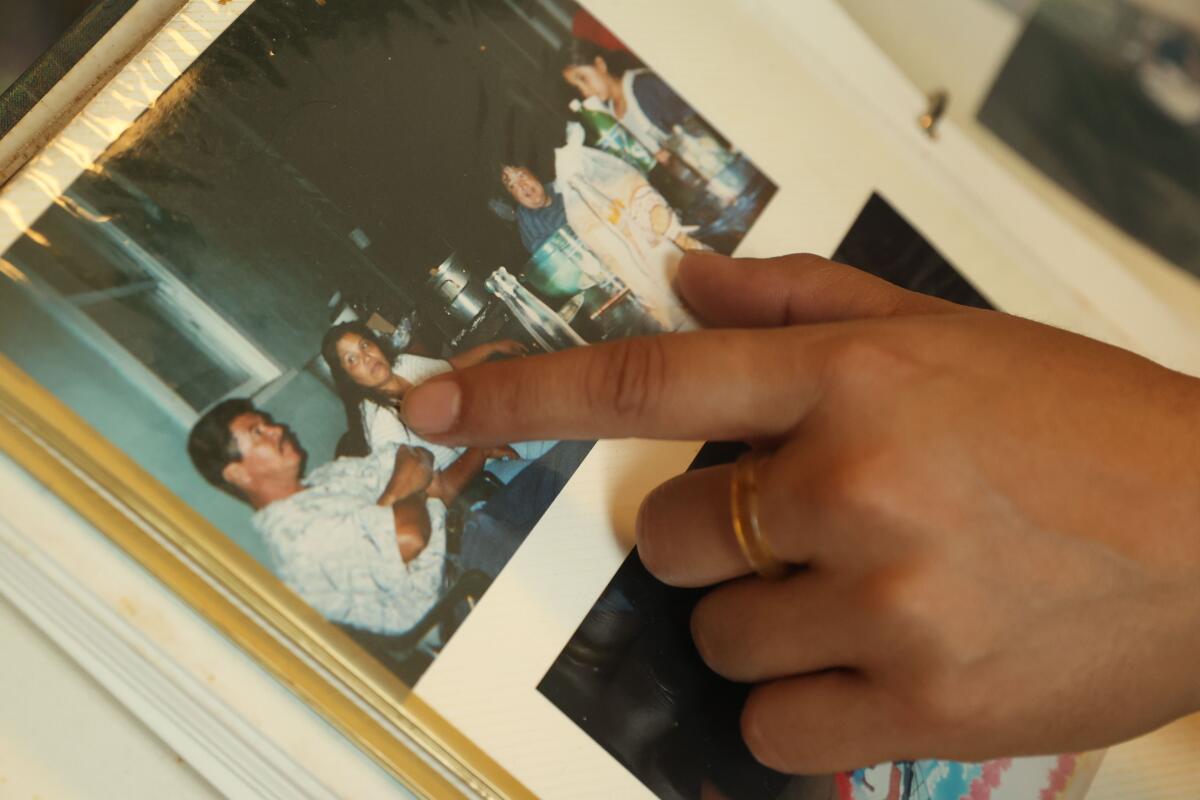

Maria Lopez shows photos of her family home when she was a child in Long Beach.

(Michael Blackshire / Los Angeles Times)

Akinnagbe and his wife, Laura, told The Times they see themselves as stewards of the aging Craftsman-style homes on the property, which are more than 100 years old. They live with their children in the front house and want to remodel the duplex in the back to rent it out as subsidized housing.

“We know housing instability personally and we do not want to contribute to the problem of housing instability in Long Beach,” Femi Akinnagbe told the council earlier this year. “Which is why we are renovating our home in order to create Section 8 housing for the most needy and vulnerable individuals in our community.”

He said he bought the property in significant disrepair and it needs to be fixed. Lopez agrees that there are repairs that should be done, but doesn’t believe she should be evicted for them to happen.

Early on, Akinnagbe said he told Lopez he hoped to raise her rent to a “market rate goal” of $2,500, which he said would make it easier to do some of the renovations. He asked her to apply for rental subsidies and grants to help cover the cost, which he said would have been a “win-win for everybody.” Lopez did not agree to the increase, which would have been significantly above state limits. As of August 2023, the maximum allowable annual rent increase under state law was limited to 8.8%. Ultimately, Akinnagbe raised her rent by that amount.

About two months after buying the property Akinnagbe served Lopez with a 60-day notice to vacate, saying he intended to substantially remodel the unit.

A description of the work included with the notice said the plan was for an interior home remodel to “remove and replace shower, vanity, toilets, sinks, countertops, cabinets, garbage disposal, electrical fixtures, outlets, flooring, painting, drywall and refurnish ceiling.”

There would be “no structural work,” the notice added.

Lopez reached out to the city to ask whether the work was sufficient to constitute a substantial remodel.

Under state and city rules, a substantial remodel “means the replacement or substantial modification of any structural, electrical, plumbing or mechanical system that requires a permit from a governmental agency, or the abatement of hazardous materials, including lead-based paint, mold or asbestos, in accordance with applicable federal, state and local laws, that cannot be reasonably accomplished in a safe manner with the tenant in place and that requires the tenant to vacate the residential real property for at least 30 days.”

The proposed work likely did not meet the standard, city officials said.

“Based on the facts as you have presented them to us, and in the experience of our Building and Safety experts, it is the city’s nonbinding opinion that your proposed project does not constitute a substantial remodel,” city officials wrote in a letter to Akinnagbe.

Then, earlier this year, the landlord served Lopez with another notice. This one added to the work, saying it would include a complete kitchen and bathroom remodel, a complete or partial removal of interior walls, creation of a new entrance and asbestos and lead abatement.

This time the city said it was “unable to confirm or deny whether the scope of work meets the threshold.”

The Akinnagbes say they didn’t change the initial plans much, but that they just didn’t understand the level of detail they were required to provide to show that the work was indeed a substantial remodel.

“We walked into this with her knowing the law and knowing how to navigate it much more than us,” Femi Akinnagbe said.

Both sides say the dispute has led them to feel unsafe on the property.

In May, Lopez was again in front of the council, this time advocating for herself and asking them to end substantial remodel outright.

She is also fighting the eviction in court based on technicalities. But she’s uncertain about her long-term chances as long as remodel evictions are permitted.

“Unfortunately, until the law is changed, the landlord does have the legal right to evict Maria,” her lawyer, Stephano Medina, of the nonprofit law firm Public Counsel said.