This story was originally published by Grist and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

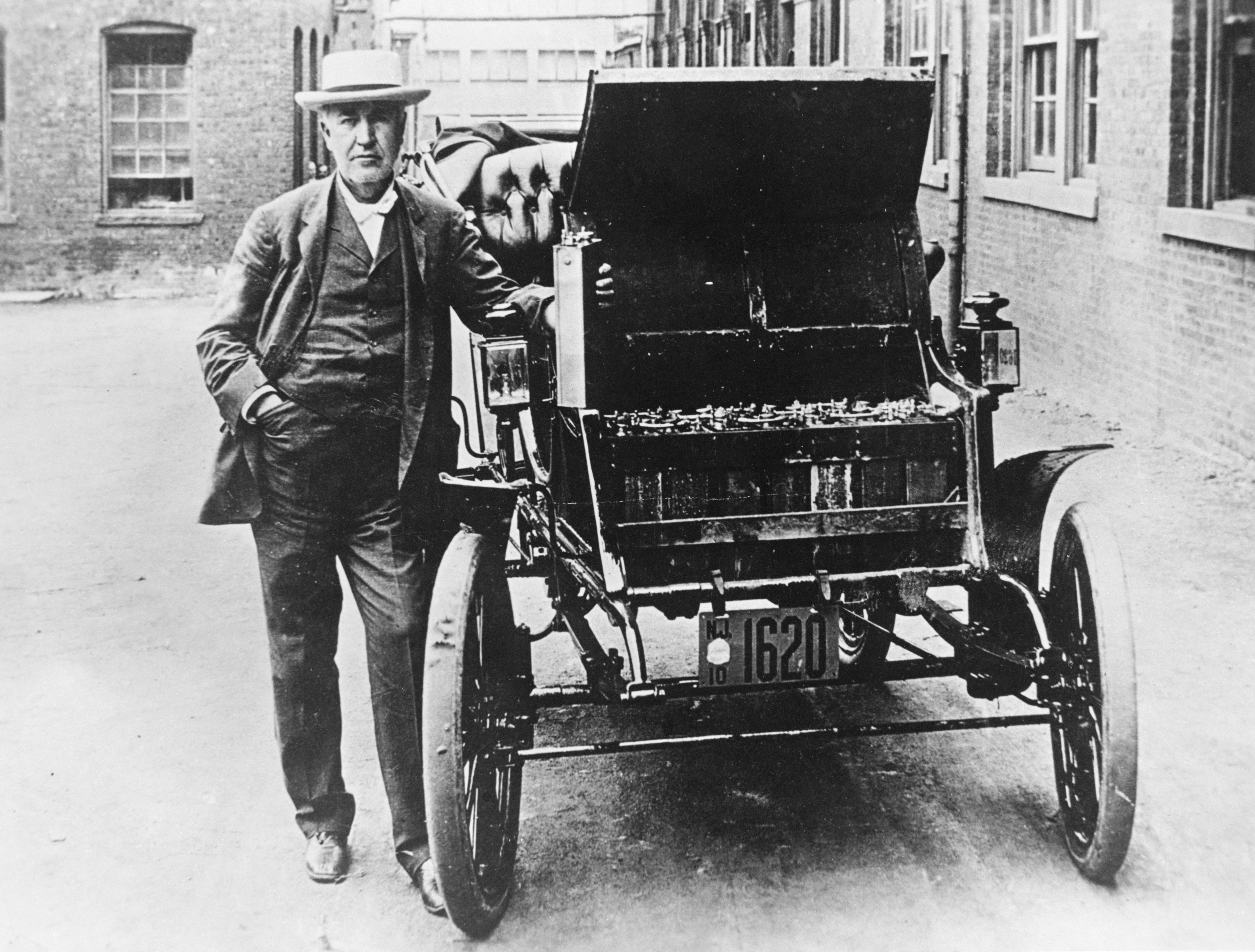

Nicholas Petris, born to Greek immigrants in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1923, could remember a time when electric trucks were a common sight on the streets of Oakland. In fact, just a couple decades before his birth, both electric and steam-powered vehicles—which were cleaner and more powerful, respectively, than early gas-powered cars—constituted far larger shares of the American car market than combustion vehicles. The electric cars of this era ran on lead-acid batteries, which had to be recharged or swapped out every 50 to 100 miles, while the steam cars relied on water boilers and hand cranks to run. But for a few historical contingencies, either model could have rendered its gas-powered alternatives obsolete.

By the time of Petris’ childhood, however, cars with internal combustion engines had become dominant. Gas guzzlers won out thanks to a combination of factors, including the discovery of vast oil reserves across the American West, improvements in the production and technology of gas-powered cars (including the invention of the electric starter, which eliminated the hand crank), the general population’s limited access to electricity, and the occasional propensity of early steam cars to explode.

Whereas electric car pioneers had envisioned communal networks of streetcars and taxis, the gas-powered automobile promised independence, unconstrained by the relatively limited distances battery-powered vehicles could travel without a charge. This meant more Americans than ever were driving on their own, rather than sharing mass transit, such as the railroads on which Petris’ father worked as a mechanic. Petris grew up in a California increasingly dense with traffic and crisscrossed by freeways.

But with the rise of combustion cars came smog. Named for its superficial resemblance to both smoke and fog, the lung-punishing, eye-burning, occasionally deadly mixture of air pollutants began settling on cities—most famously Los Angeles—in the mid-20th century. In 1949, for instance, a blanket of ammonia-smelling vapor settled on Petris’ hometown; a newspaper in nearby Palo Alto, where Petris was studying law at Stanford, declared smog “a growing menace.” By the early 1950s, scientists had identified its cause: exhaust from gas-powered cars. Legislators and regulators—especially in California, the biggest auto market in America—raced to limit the fumes that cars were permitted to spew into the atmosphere.

The “internal combustion engine is pouring out poison,” Petris told reporters. “So why not limit it?”

In 1958, a still-youthful Petris won election to the California Assembly and was immediately placed on its transportation committee. Just months later, the legislature ordered the state department of public health to establish air quality standards such as maximum allowable levels for auto pollutants. In 1966, the year Petris won election to the state Senate, a California agency required all new cars to reduce certain pollutants in exhaust. Yet federal clean air standards remained far weaker than California’s, and Detroit-based car companies expended tremendous resources aimed at slow-walking regulation. Industry representatives begged for delays, claiming they needed more time to improve pollution-control technology.

Over the seven years Petris spent in the legislature’s lower chamber before his election to the Senate, he had been fielding a steady drumbeat of constituent concerns about air pollution. Doctors showed up at his office begging him to do something about the brownish haze poisoning their patients. He read of the thousands who died from breathing polluted air in Los Angeles alone. A turning point came when a scientist brought Petris a report attributing his state’s infamous smog problem to the automobile and suggesting that, despite its protests, the auto industry had the tools available to reduce its emissions. Despite seven years of incremental legislative progress, Petris realized the government hadn’t done nearly enough. “Oh, we can’t wait any more,” he would recall remarking. It was time, Petris concluded, for something “extreme.”

On March 1, 1967, the newly elevated state senator announced his intention to introduce a bill that would limit each California family to just one gas-powered car beginning in 1975. “[The] internal combustion engine is pouring out poison,” Petris told the press. “So why not limit it?”

The press responded with scorn. Petris’ hometown newspaper, the Oakland Tribune, dismissed his proposal as “so ridiculous that it is difficult to select from the variety of arguments that demonstrate its absurdity.” Even the senator’s campaign manager was furious. Yet rather than watering down his bill, Petris altered it to simply ban all cars with internal combustion engines by 1975.

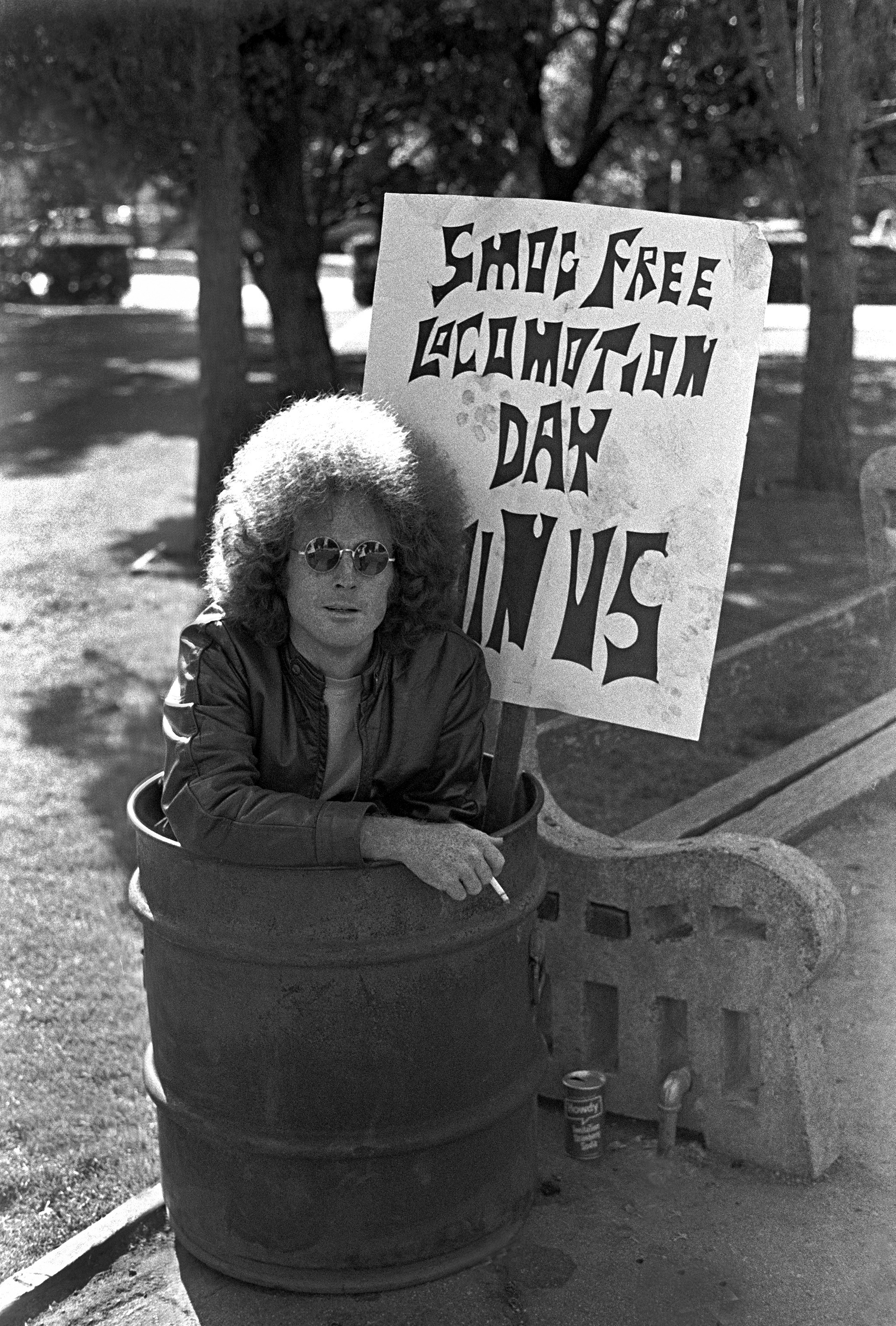

California’s other legislators were uninterested, so Petris asked merely that his Senate colleagues study the subject further during the legislative recess, during which time he could regroup. Few of these colleagues could have suspected that Petris’ crusade was just beginning. In fact, in the years to come, the California legislature would come shockingly close to heeding his call and banning all gas-powered cars. Copycat efforts would erupt across the country and within the US Congress. For a brief moment, Petris’ pipe dream would be at the vanguard of the burgeoning environmental movement.

“We want to scare hell out of the industry,” said a New York state legislator. “We want them to come up with a clean alternative, now.”

As we now well know, this fight to ban the internal combustion engine ultimately failed, stymied by aggressive auto industry lobbying. But more than 50 years later, history appears to be repeating itself. Late in the summer of 2022, a California state agency announced a ban on the sale of new cars containing internal combustion engines. This ban, set to take full effect in 2035, ignited explosive reactions across the political spectrum. In a matter of months, almost a dozen other states had followed suit, enacting bans modeled after California’s, and the European Union appeared poised to do the same.

As it had a half-century earlier, fierce pushback came from the auto industry and its political allies. In Europe, the government of Germany (home to several powerful automakers) forced a wide loophole into the ban, and other countries (including Italy, home to other big car companies) are now pushing to delay implementation. In the United States, the House of Representatives passed a bill to strip all states of their ability to impose such bans. Though the Senate has not done likewise, the Supreme Court may well be preparing to eliminate California’s authority to set tougher auto emissions standards than the federal government, a position that former President Donald Trump would undoubtedly support if he wins another presidential term in November.

Largely unmentioned in this ongoing fracas is the fact that nearly all of this—California leading the charge to prohibit gas-powered cars, other governments following suit, intense industry resistance—has happened once before. Petris’ crusade, though it made the front pages of newspapers across the nation, is little-remembered. Yet the history of his fight and eventual failure has only taken on increased relevance as climate change has revealed the necessity of decarbonizing transportation, which accounts for almost a third of US greenhouse gas emissions. Never-before-cited archival material documenting this lost history reveals vital lessons for an effort whose time, a half-century later, may have come at last.

It was a warm, clear Wednesday in March 1969, two years after Petris’ bid to limit and then ban gas-powered cars had apparently died a quiet death, when the state senator reintroduced his bill—and received a very different reception. Just weeks earlier, the largest oil spill in US history had begun off the coast of Santa Barbara, and the California legislature had recently concluded hearings that criticized American automotive companies for failing to tackle smog. This time Petris cannily decided to submit his bill not to the Senate transportation committee, as in his initial attempt, but instead to the much more welfare-oriented health committee. The bill proposed to add the following language to California’s health and safety code: “On or after January 1, 1975, no motor vehicle powered by an internal combustion engine shall be operated on the highways of the state.”

The big car companies “laughed at first,” Petris later recalled, their lobbyists writing off the bill as too radical to merit opposition. But, as contemporaneous reporting and documents in the California State Archives show, Petris brought in doctors to tell the health committee about the “violence” smog enacted on the human body; he brought in William Lear, creator of the Lear Jet, to talk about advances in steam-powered car technology. Supportive letters poured in. On July 24, the health committee unanimously approved the bill. Late that evening, in a move even Petris acknowledged to be a “surprise,” the full Senate passed it by a vote of 26 to 5. The senators had amended the bill only slightly, to have it ban the sale of gas-powered cars in 1975, rather than their possession.

Detroit went crazy,” Petris recalled in another oral history interview. The big car companies deluged the state with lobbyists and money; they mobilized the state’s car dealers’ trade association, which sent an “all-out alert” to local members, rallying them against the bill. The state chamber of commerce, in turn, condemned the bill’s “serious economic consequences.”

But California residents mobilized, too: In Los Angeles, a group of mothers and children picketed outside a General Motors plant, telling the press they supported the bill. Ultimately, the issue reached a boiling point in a seven-hour hearing before the Assembly’s transportation committee; the chamber was packed with high-priced lobbyists and irate car dealers. As the clock approached midnight, Petris realized he was going to lose by a single vote. He tried to soften the bill’s language to persuade the last legislator, changing an outright ban to an effective one via stringent emissions standards, but to no avail.

In multiple polls conducted in 1969, more than 60 percent of respondents favored banning the internal combustion engine within a few years.

Nevertheless, the bill’s opponents did not revel in their victory. “The damage has been done,” lamented one San Jose car dealer. “The car is now looked upon like some kind of dangerous drug.”

Indeed, even before his bill died in the California Assembly, Petris had begun traveling the country, urging other legislators to try to ban the internal combustion engine. Soon, copycat bills appeared in Arizona, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawai‘i, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, New Mexico, and Washington.

“We want to scare hell out of the industry,” a New York legislator told Washington Monthly. “We want them to come up with a clean alternative, now.”

Multiple members of Congress also introduced copycat bills at the federal level. One would have phased out gas engines by 1978; another sought to ban them outright within three years. The federal bill that attracted the most support was that proposed by Democratic Sen. Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin, the founder of Earth Day. His bill was fashioned as an amendment to the Clean Air Act, which was being debated in 1970.

“I do not believe that the automotive industry will shift to a low emission engine unless the Congress acts and requires it by statute,” Nelson wrote in a contemporaneous letter.

Perhaps the most surprising fact about the whole saga is just how popular the campaign to phase out gasoline-powered cars was among members of the public. Multiple polls in 1969 found that more than 60 percent of respondents favored banning the internal combustion engine within a few years. Supportive letters and petitions streamed into Nelson’s office. Newspaper editorial boards, including that of The Washington Post, endorsed Nelson’s bill.

“Given a choice between the fetish of the automobile and suffocation, at least some would prefer to go on breathing,” declared The Tennessean. In California, a group called The People’s Lobby gathered a reported 425,000 signatures in an attempt to put the issue on the ballot so that state residents could vote on Petris’ proposal directly.

Bending to popular will, Mercedes started experimenting with hybrid electric buses, while General Motors tried out next-generation steam-powered cars. Even then-President Richard Nixon, in a 1970 address to Congress, announced the creation of a public-private partnership “with the goal of producing an unconventionally powered, virtually pollution-free automobile within five years.”

Among the loudest supporters of Senator Nelson’s bill was the United Auto Workers, one of the most politically outspoken and vocally environmental unions in the nation. “I do not believe we can live compatibly with the internal combustion engine,” declared Walter Reuther, the union’s president, in 1970. As public statements and unpublished documents in the union’s archive memorialize, UAW officials demanded cleaner cars despite the fact that it could theoretically put union members’ jobs in jeopardy.

“We’re concerned first as citizens as to the poisoning of the atmosphere, obviously,” Leonard Woodcock, Reuther’s successor as UAW president, told NBC’s “Today Show” later in 1970. But he was confident that the transition to clean cars would actually create more jobs for UAW members, rather than fewer.

In fact, he thought that public outcry over the dangers of auto emissions could reach such a fever pitch that car production would be jeopardized if the industry didn’t find an alternative. UAW members themselves told legislators that they wished fervently for better jobs, hoping to be freed from the horrific health and safety conditions that predominated in auto plants.

As they had in Sacramento, auto industry representatives descended on Washington to fight Nelson’s bill. Publicly, they blasted the senator as ignorant, having “little or no knowledge of the facts of automobile design.” Nelson lamented the effectiveness of such attacks. “The chief obstacle to more stringent control of the internal combustion engine or to developing alternatives to it,” reads one memo in his archival papers, “has been the auto industry itself.”

All of the bills, state and federal alike, failed in the end. Nixon’s program to create a “pollution-free automobile,” meanwhile, was underfunded and soon folded. The car companies quietly shelved their greener experiments, and much-vaunted private efforts—such as William Lear’s steam car—couldn’t attract sufficient financial backing to become true market competitors.

Yet the midcentury crusade to eliminate the internal combustion engine was not a complete failure. In California, Petris pivoted quickly, throwing his support behind the most stringent emissions standards he could get. “I’m a realist,” he told the press. “So I settle for the next best thing.” Soon the California Air Resources Board—the same agency that 50 years later would announce a phaseout of gas-powered cars—adopted the strongest emissions regulations in the nation, which effectively forced auto companies to begin installing catalytic converters en masse.

“Better we tear the factories to the ground,” wrote one UAW regional director, “than continue this doomsday madness.”

Nationally, Senator Edmund Muskie—the legislative force behind the Clean Air Act—introduced a bill requiring automakers to reduce pollutants by 90 percent by 1975, the very same deadline Petris and Nelson had set in their crusades. Despite fierce industry lobbying, that bill passed, and a reluctant Nixon signed it into law. “I won after all,” Petris later told an interviewer. But in the years that followed, industry lobbying successfully pushed the EPA to extend the deadline. In 1973, the U.S. was hit by an oil embargo from the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, which battered car companies’ bottom lines and gave them an argument for further delays.

Nonetheless, the companies significantly reduced emissions in the following years, leading to “99 percent cleaner” vehicles compared with 1970 models, according to the EPA. A study commissioned by the agency found that, in the two decades following its passage, the act saved hundreds of thousands of lives and trillions of dollars.

Today, as the fight to ban the internal combustion engine is in the headlines once again, the story of Nicholas Petris’ fight for an emissions-free engine is instructive: It takes state pressure to get industry to shoulder the expense of innovating cleanly, and it takes public pressure to turn a zany bill into a national movement.

Conversely, however, even national popularity can fail to realize legislative or legal success in the face of concerted industry opposition. As the recollections of Petris, Nelson, and many others testify, the Detroit car companies were deft and dedicated opponents of the bills to ban the internal combustion engine, and their resistance stymied the most far-reaching efforts to curb auto emissions. This history, then, counsels constant vigilance for the proponents of contemporary efforts to phase out the gas-powered car. Even the passage of the Clean Air Act did not stop beneficiaries of the status quo from slow-walking change at every step.

Above all, this history demonstrates the power of solidarity in the fight for environmental change. Even at the expense of their own convenience, members of the public united to demand a different world. “I will sell bicycles if I have to,” one car dealer reportedly wrote in a telegram to Petris. “You go get ’em.” Leaders of the UAW—a union definitionally dependent on the automobile—threw their support behind a bill to ban the very thing they produced; some called for expanded mass transit, and some went much further still.

“Better we tear the factories to the ground,” one UAW regional director wrote of the pollution problem, “than continue this doomsday madness.”

In the years following the defeat of Petris’ bill, however, the UAW dropped its environmental advocacy. The energy crisis, the escalation of union-busting, the spread of offshoring, and the rise of Ronald Reagan united to deradicalize the union, and by the late 1970s it was lobbying for weaker emissions standards. Yet in 2023, in the UAW’s first direct election, the radical candidate Shawn Fain became the union’s new president. Fain, known to sport an “eat the rich” T-shirt, has since led a drive to unionize the electric-vehicle sector.

“We have to have a planet that we can live on,” Fain told a rally. It’s a message that evokes both a long-lost past—and a hopeful future.