When James Cameron wrote ‘the future is not set’, he wasn’t kidding. The year was 1982 and Cameron — then a Roger Corman-schooled production designer, art director, effects guru and general Jim of all trades — was in Rome, directing a few ill-fated days on Piranha II before getting the boot, when a vision came to him in a fever dream. It was a hellish image, of a chrome skeleton, an unstoppable robot that Cameron decided was from the future. He called it, and the movie it inspired, The Terminator.

When he got back to Los Angeles, licking his wounds, Cameron started writing the screenplay for a movie in which that unstoppable robot travelled back in time to try to kill the mother of the leader of a future resistance. It included that line, ‘the future is not set’. Which, for Cameron, wasn’t so much a line, more a mission statement. “You seize the day,” he tells Empire. “You don’t come to watch, you come to play. Those are principles that I apply to myself.”

And how. These days, Cameron is arguably the most successful director of all time. Three of the biggest movies of all time (Avatar, Titanic, and Avatar: The Way Of Water) are his. He has three Oscars. And virtually all his movies — including Aliens, The Abyss, and True Lies — are considered to be classics.

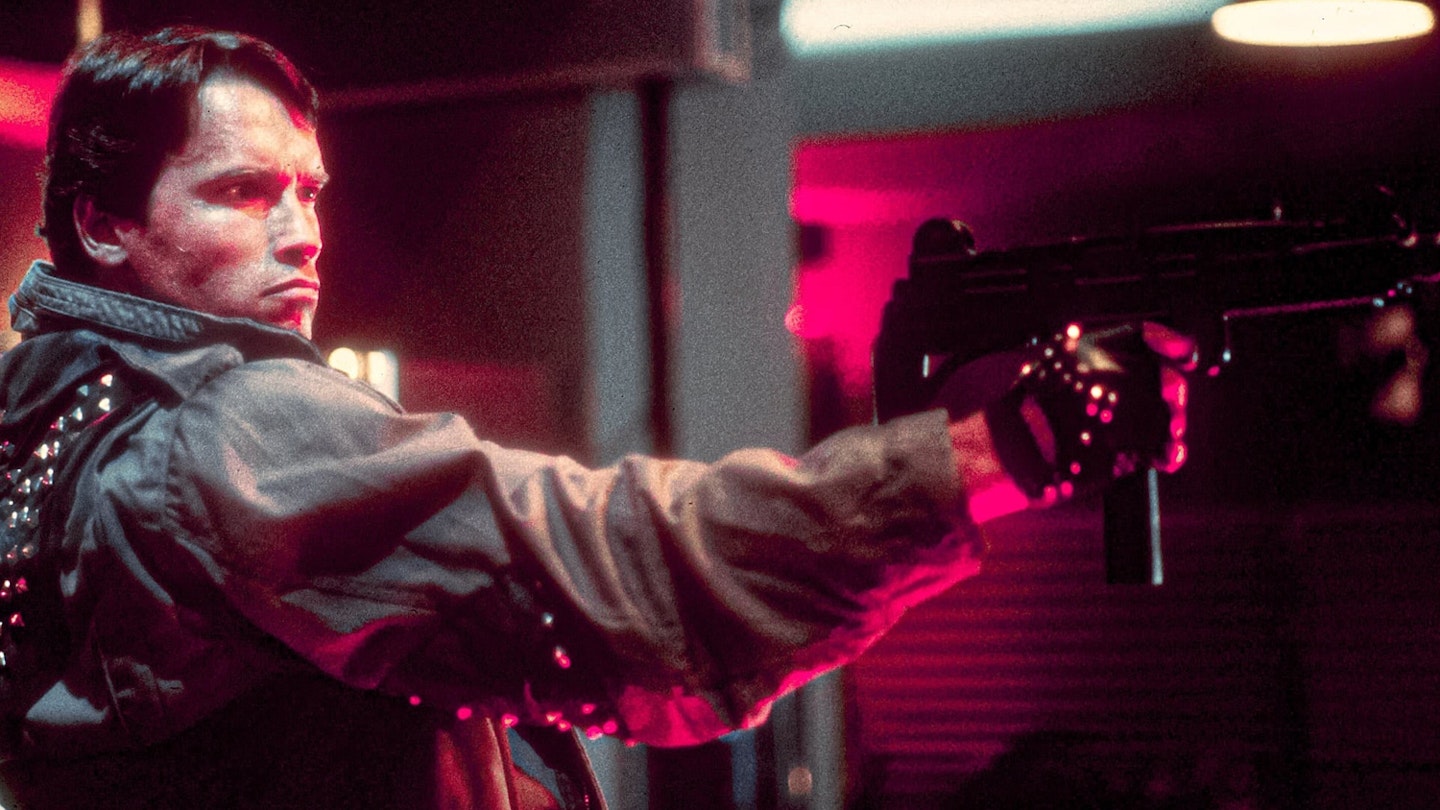

And it all began with The Terminator, the movie that also catapulted its star, Arnold Schwarzenegger, to mega-fame after its debut in 1984. It was tight, taut, and incredibly intense. Seven years later, Cameron and Schwarzenegger (and Linda Hamilton, as Sarah Connor), repeated the trick with the pumped-up blockbuster behemoth that is Terminator 2: Judgement Day. After that, Cameron left the franchise, which then endured diminishing returns with a raft of inferior sequels, before returning to produce Tim Miller’s lukewarmly-received 2019 legacy sequel, Terminator: Dark Fate.

These days, Cameron’s future is a little more set than most — the Avatar sequels have him booked up for the rest of the decade — but over the course of nearly two hours on Zoom, his focus is firmly fixed on the past, and The Terminator’s latest milestone.

EMPIRE: The Terminator is 40 years old. Which ain’t bad for a fever dream in a cheap Rome hotel.

JAMES CAMERON: A cheap pensione in Rome, and you know, I was just a punk starting out when I directed The Terminator. I think I was 29 at the time, and it was my first directing gig. I’d gotten fired off Piranha II after a few days of shooting, so I don’t really put that on my CV, even though other people love to remind me all the time. But Terminator was my first film, and it’s near and dear for that reason. But I think I can look at it pretty objectively now as a creature of its time, both in terms of how it sits in the zeitgeist of that moment, and also how it sits in my career as a first effort. I don’t think of it as some holy grail, that’s for sure. I look at it now and there’s parts of it that are pretty cringeworthy, and parts of it that are like, yeah, we did pretty well for the resources we had available.

What are the parts that make you cringe?

Oh, just the production value, you know? I don’t cringe on any of the dialogue, but I have a lower cringe factor than, apparently, a lot of people do around the dialogue that I write. But fuck them. You know what? Let me see your three out of the four highest grossing films, then we’ll talk about dialogue effectiveness.

And what are the parts that make you proud?

I don’t know if it’s proud, because so much of it in retrospect, you realise, is kind of luck and serendipity. I’m not talking about the intention stylistically, because I think I really did have a good sense of what I was doing there, surprisingly for a first time out. I guess, seeing that Arnold could be that guy. I’m proud of our ability to pivot from seeing the guy as a nondescript face in a crowd that wouldn’t stand out, to the most outstanding guy that you can imagine. I think a lot of filmmakers, especially first-time filmmakers, get very, very stuck in a vision, because of insecurity. I’m proud of the fact that we weren’t stuck enough to not be able to see how it could work with Arnold, because it wasn’t our vision. Sometimes, when you look back from the vantage point — at this point 40 years — we could have made a great little film from a production value standpoint, and it would have been nothing if we hadn’t made that one decision that captured the imagination of people.

“When he says, ‘I’ll be back’, an audience who had never seen the film before laughed.”

Did you tailor it for Arnold once he came on board?

Nothing was tailored for Arnold. We didn’t change a word of the script for Arnold. It’s just the entire tone inflected in that moment. It didn’t lose its seriousness, it wasn’t really played for humour, but there was some irony that emerged. When he says, ‘I’ll be back’, an audience who had never seen the film before laughed. Now, why are they laughing? Because the film has already, up to that moment, promised you that there’s an irony to that line. ‘Yeah, he’s gonna come back and you’re gonna fucking regret it.’ So, to me, that’s a film that’s really working. Nobody was more shocked than myself that people laughed at that line. I think when I wrote it, I didn’t even think that it would play that well. I just thought it was a throwaway. So movies have a life of their own.

Is that something that you detected on set? That gold was being mined? That the movie was taking on a life of its own?

Absolutely. I remember our first day’s dailies with Arnold. We ran them again. It was like, ‘Run that shit again!’ He was in the police car searching for them [Sarah Connor and Kyle Reese], he’d just been flash-burned so his hair was much shorter at the front. He had kind of bangs. It was very 80s. His eyebrows were burned off, which was done with a thin prosthetic. Stan Winston put a pale makeup base and a little bit of a glycerin sheen on it, so he had almost a plastic quality. And he’s lit by the dashboard light, which is killing all the pigment colour in his skin. And I had asked him to do something, because Arnold was very directable in the sense that he wanted to bring everything possible, but he needed an outside perspective. I said, I don’t want you to look like a person looks where you lead with your eyes. I want you to lead much more in a shark way. I want you to look first, then turn, then look, then turn, not simultaneously. So he’s driving, he’s got this makeup gag, this very cold lighting, and it’s a 100 milllimetre close-up on a hood mount, I think it was, and there was also a fixed camera when he pulled up and stopped. And we just watched the shot and I was like, ‘Motherfucker, this is working. Holy shit. Run that again!’ It was our first day’s dailies with him, and we were ten days into the shoot. There’s always a moment on any film where you know you got something and that was the moment.

That’s interesting, because the last time we spoke, at an Empire VIP Club event, you said you got on really well with Arnold after, and I quote, ‘the first day of terror’.

I’m not sure exactly what I meant by that. I’m guessing now, after the fact, that it was about my apprehension. “I’m about to start directing Arnold Schwarzenegger. He could be a giant asshole!” And he wasn’t. He’d starred in these Conan films and he was Mr. Universe 29 times or whatever it was, and he could have been a giant prima donna. He didn’t turn into that until much later. Now, Arnold knows I’m kidding. You know I’m kidding, right, Arnold? No, he and I are still besties, and I like to wind him up a little bit, and he likes to wind me up. But he was great, and he came with a will to make it everything that it could be.

But you must have known that he wasn’t a prima donna or an asshole when you first met him.

I knew that. But look, you’re going into your first film, you’re dealing with a big star. He was a million dollar guy on a six million dollar movie. He outweighed me ten to one. They’d have fired my ass — they had a guy waiting in the wings — if I screwed up in the first few days.

Do you know who it was?

Probably some old hack that they knew they could push around. I was young, I was unproven, I was brash, I was difficult to deal with. You know, they would have loved to get rid of me if they could. I just had to give them the slightest excuse. So I knew I had to make my days and show some footage that looked good so they didn’t have a big enough reason. I had a fever of 103 on the third day of shooting, and it was the scene where Reese goes through the entire department store with the cops after him. And it’s just one tracking shot after another after another, and it was freaking delirium. I don’t even know what I did. I don’t even have a memory. I do remember at one point, ‘Okay, get the dolly over here and we’re gonna run underneath all the clothes and see him scrambling along’. It was just freaking delirious. But they couldn’t fire me.

Do you remember your first meeting with Arnold?

Arnold’s version of the story, by the way, that he has recounted since, is wrong. Gale’s [Anne Hurd, Cameron’s producer and co-writer] is wrong. Gale, mad respect, but she wasn’t even there. It was me, Arnold, and Barry Plumley, this jerk-off pal of John Daly, who ran Hemdale. The ‘dale’ of Hemdale. Barry Plumley was this complete doofus who was supposed to be a producer, but he didn’t think like a producer. He was a bon vivant, a social butterfly pretending to be a producer. So it’s Arnold sitting to my left, Plumley sitting to my right, kind of diagonally on a bench seat. We’re at Le Dome [LA restaurant; now closed], and Arnold starts talking about all the scenes he loves in the script, which happened to be Terminator scenes. And I keep trying to bring it back around to Reese, and Reese’s character, and I want to hear Arnold’s take on Reese. Arnold’s not talking about Reese.

“I wasn’t thinking of him as The Terminator. It didn’t fit our vision.”

Now, there’s two possible explanations. One is, he’s gaming me, getting me to think about him as the Terminator. Or two, he just genuinely loves the story and wants to be a part of it. Maybe subconsciously he knows that having 20 pages of expository dialogue, rapid fire in unaccented English, is probably not his main meat. I honestly do not believe Arnold was angling for the Terminator part. I think he was honestly just enthusiastic about the film, and wanting to be in it. But I gotta set the stage for this lunch.

I’m leaving my little apartment in Tarzana, in my dad’s car, which I had borrowed for a year, and I’m racing across town to Le Dome to have a meeting with Arnold. And as I leave, I say to my roommate Bill Wisher, who is a guy that I had been doing some writing with, ‘Do I owe you any money? Because I’m probably not going to survive. I gotta go pick a fight with Conan.’ Because I didn’t want Arnold in the movie. I didn’t want him to play Reese. It didn’t make any sense. This was coming from on high at Orion that Arnold should play Reese. It was just a stupid idea. Arnold was not a verbal performer at that time, you know? Eventually he’s done umpteen films and he’s great with dialogue and all that, but he wasn’t at the time, or at least we certainly didn’t perceive him that way. I wasn’t thinking of him as The Terminator. We had talked briefly about the idea about six months before, myself and Gale, and we thought, man, maybe not. It didn’t fit our vision. He’s not going to be able to disappear into a crowd. He’s going to be Arnold. It’s not going to work, right? So we discounted it and I went in [to the lunch] with a mindset of just ticking the box. I’m going to tick the box and come back and report that it doesn’t work. You’re getting the straight poop here. Everybody else’s story is bullshit. By the way, Arnold’s version of the story is that he was the one that got the idea that he should play the Terminator. Absolutely wrong. He did not. It happened while we were at lunch, and it happened internally with me, and we never even discussed it until I had that left that lunch and gone back and met with Gale and John Daly afterwards.

So I’m sitting there, and Arnold’s talking away about the script and how this works, and how that works, and the sound just goes out of the shot. I’m just watching his face. I’m thinking he could be like a human bulldozer. He could be like a Panzer tank. It would just be different. But man, it would be powerful. I’m talking to myself — ‘Yeah, but it’s gonna fuck up the entire idea. He’s supposed to be an infiltrator. That’s why they gave him skin in the first place, and bad breath, and hair, so he could be an infiltrator. He’s not gonna be an infiltrator, it’s not gonna work, it defies the entire concept of the writing.’ But I’m just watching and thinking, ‘Fuck, it would be monolothic.’ So, come time to pay. And when I was leaving my apartment, I had a pile of cash — not a big pile, because I was dirt poor — in my desk drawer, and I meant to grab it so that I could buy lunch, because somebody told me somewhere, or I read that you’re supposed to, if you’re a big shot producer/director, buy lunch for the actor. And I was two blocks away and I was already late, or projecting to be slightly late, and I went ‘Fuck it. Punctuality is more important.’ Anyway, Barry Plumley will be there, he’s an executive producer, he could put it on the Hemdale tab, right? I debated turning around, going back, grabbing the cash. This is the kind of level we were at. I was like, ‘No, I just gotta be on time’. So I raced across town. Cut to the end of the lunch. I’m like, ‘Alright Barry, you gotta get the check, buddy’. And Barry’s like, ‘Oh, mate, I left my wallet on my desk’. And I’m like, ‘You fucking idiot’. So the director and the executive producer show up and Arnold’s gotta buy lunch for us! Arnold just laughed it off. He said, ‘Yeah, I was in a similar situation once,’ and he told this whole story about meeting somebody big and important and they didn’t have their wallet and he wound up having to pay for it. It was all funny, you know? I thought, what a gracious guy.

I had a completely different impression of him coming out of the meeting than what I had gone in with. He and I hit it off at that lunch. So, I go back to report to John Daly, and drive over to the Hemdale offices on Sunset Boulevard, and Gale’s there. They’d been in some kind of meeting. And I said, ‘He’s not Reese, it was a bad idea… but he’d make a hell of a Terminator’. Quote. There’s no surveillance camera there to prove it. And Daly doesn’t miss a beat. He’s standing in the middle of the room between his desk and the couch where Gale and I are sitting. He spins around, picks up the phone, calls Lou Pitt, Arnold’s agent. He says, ‘We’d like Arnold for the Terminator’. There’s this long pause. He says, ‘Well, yes, I know, Lou. Yes, I understand that he doesn’t have much dialogue. There’s not very much on the page, we understand. But he is the title character, Lou.’ This goes on for, like, fifteen minutes and finally Lou turns the whole thing down. I find out 24 hours later that Arnold has fired Lou Pitt — he subsequently hired him back, and Lou and I got to be friends. Gale eventually signed with Lou Pitt! He turned out to be a great guy. But he was dead wrong in this scenario, and Arnold fired him. I don’t know what he said, but something to the equivalent of, ‘You fucking idiot, I wanted to be in that movie, and I’ll play that guy’. So then a deal got struck, and we were on.

The only problem was, Arnold turned out not to be available in the exact year that we wanted to shoot the film, which was summer of 1983. We’d done all our prep for that. He wound up not available until February of 1984, which kind of worked out in my favour, because that’s when I wrote Rambo [First Blood: Part II] and Aliens, or at least bit off a big chunk of Aliens, enough to keep the job. Before, I had been busy on The Terminator. So that’s the whole story. There’s some small merit to Arnold’s perspective, yes, but it’s a big revision of history to say that he talked me into it. You heard it. This is the straight shit. My mind is like a freaking surveillance camera. You can count on this. You can take it to the bank. And by the way, there’s no way to prove this.

Was that emblematic of the shoot? You’ve had challenging shoots throughout your career, but I’m betting The Terminator was the first time you had money problems.

We didn’t have much of a budget, but they never didn’t cash flow. There was another company out there at the time called Cannon that didn’t pay their crews, ran out of money halfway through shoots, all that sort of thing. Hemdale had the money. They committed it. The question was, were they going to keep me on as director? But I managed to get through the shoot. We finished the schedule on time, but we didn’t have the whole movie. We just didn’t tell them that. I got 40 grand to direct the movie, and I put of that, oh let me see, forty grand into reshoots. That took us a week, and Gale put some money into it. We scheduled one week of reshoots. I don’t even think we told Hemdale we were doing it, or maybe they knew about it, but as long as we were paying for it ourselves they didn’t give a shit. Even on a Terminator budget, a week of reshoots would have cost you half a million bucks. So we had to do it for a tenth of that, which we did.

I called in every favour. I got a stage from a friend of mine that was running the stages for Roger Corman. It was a shed that was used to store plywood, it wasn’t even a stage. I called in favours, operated the camera, lit it all myself, scrounged up some lights from Corman’s back lot on a don’t ask, don’t tell, wink and a nod kind of a deal. We got Arnold to come back and Linda to come back for free, Stan Winston showed up with his guys, we didn’t have to pay him. And we just did a bunch of inserts. The whole factory scene, the feet on the stairs and the bomb going into the body and the body blowing up and the Terminator’s head getting crushed, all that stuff was done in that week.

“They could have fired me on the spot. But you know, they’re idiots.”

The problem is, we either didn’t have a chance to get it cut in or we hadn’t shot it yet, but we had to show the movie to Hemdale and Orion. I wasn’t even smart enough to take my storyboards and film them and cut them in. We never did shit like that at Corman. We never did anything that was wasted energy. I had the storyboards. I should have shot them and I should have cut them in so they could have seen what the scene would be like. And the entire last reel of the movie, every other shot was a slug. So we showed them the movie and I go up to [John] Daly’s office, and they’re all ashen-faced. I get this ashen-faced thing a lot. You should have seen on Avatar, by the way, the first time they saw that film. Seriously, six people in a room, all looking like Russia had launched and you have twenty minutes to live.

So I walk in, and everybody looks like that. Daly turns around, or maybe it was Mike Medavoy, I can’t remember, and says, ‘When the gas truck blows up, and the Terminator burns, end of the movie. Cut to credits.’ I said, ‘Guys, remember the whole conversation we had where I said, the movie’s not ready to be viewed yet, and you assured me that it was okay? I trusted you, to show it to you as a work in progress, and now you’re fucking me. Guess what? That’s not where the movie is going to end. And if you don’t like that, you can fire my ass’. And I walked out, and for some reason they didn’t. It was a real tricky moment in the whole process. Jesus, I mean, they could have fired me on the spot. But you know, they’re idiots, they didn’t know how to finish the film. They didn’t know how to rustle up some director. Our post-production was so ludicrously short that the week they lost trying to find somebody to take over would have been fatal. I think I knew that.

One of the things I think gets overlooked about The Terminator, in amongst the action and the Arnold of it all, is its emotion. You said earlier on that people criticise your dialogue. But if, ‘I came across time for you. I love you, Sarah, I always have’ isn’t the most romantic line of all time, then I don’t know what is. But that line could have been cheesy. That could have gone wrong.

Look, all my stuff can be cheesy, and some people think it is. Fortunately, not the majority. I’m not afraid to have my films wear their heart on their sleeve. What I’m not good at is, and I don’t mean this as a criticism because I celebrate it, that kind of Shane Black, smart-alecky kind of writing which has been adopted as an entire aesthetic by Marvel. People love it, they love that smart-alecky stuff, but it’s not what you’d really do in that situation. Because my whole approach to science-fiction is, the more outlandish a story, the more real you have to ground it in how people really talk, and how they really would respond if something like that was really happening to them. That’s just my modus operandi. Titanic is a wildly romantic story, but I still played it as real as I could from the perspective of the characters.

So, Michael Biehn captured the perfect quintessence of the guy. He’s deeply scarred. He’s verbal in a way that he conveys the darkness of the future and the life that he led, and all of that leads up to that line. When he tells her that he loves her, it’s so abject. There’s no arrogance. There’s no toxic masculinity in it whatsoever. It’s just raw, it’s real, and it grabs you. It’s a tribute to me, casting him. It’s a tribute to him, pulling it off and doing it. And it’s a tribute to the editor who cut the scene together. However much time he left after the line is said, because there’s almost a defeat in the way he says it, there’s a resignation. And so Linda’s reaction is part of that. It makes the line play.

Kyle and Sarah only have a few hours together. That’s Jack and Rose in Titanic as well.

All my movies are love stories. Just different types of love stories. You know, parental love is as powerful, if not more powerful, than romantic love. I’ve got a couple movies that deal with that. I’ve got parental love, even though it’s a surrogate parental love, in Aliens. I wasn’t a parent when I wrote that. I didn’t even get along with my parents that well when I wrote that, but I was writing about something that I wanted, or that I could imagine. It’s all about imagination. But imagination also has to be an emotional imagination. You have to imagine yourself in moments, in relationships that you haven’t been in. I hadn’t been a parent at that point, but I could imagine that that might be the most powerful and profound form of love that there is. And when it came true in my life I realised that was, in fact, the case. Somehow I had already anticipated what I was going to feel like years and years later. I never thought I was going to be a breeder. I never thought I was going to be a father. It just wasn’t even on my landscape. It wasn’t until I rafted up with Linda and she was obsessed. ‘Okay, we’re having a baby!’ I’m like, ‘Really? Okaaaaay. Your project!’ Then I realised that’s what fatherhood is all about, and that informed my writing after that. The Avatar films, the new ones, two, three, four five, very much wouldn’t be what they are without my experience, not only as a parent of babies and toddlers, but of teenagers, reconciling yourself to these independent lives that you’ve somehow brought into being, but have no control over.

Over the years, has your opinion of your Terminator films changed with each passing anniversary?

I look at each of those films as a slice of the cultural media zeitgeist of its time. The Terminator wasn’t the first action film of the 80s. It was one of a group of action films, most of which came later. Army of one, giant body count, it was part of a zeitgeist. Terminator 2, there was a shifting consciousness. It was also just a better made film. Physically better made, better realised. I look at them as moments in a career for me as a storyteller, that have specific meaning to me as well. Could I, with where I am now as a person, after all these school shootings, write The Terminator right now and get excited about it and want to go make it? No. I’m a different person, and that’s fine too. That’s the way it should be. We should evolve as artists. We should evolve as a society.

That’s already present in Terminator 2, though, with the kinder, gentler Arnold, and the idea that people would become emotionally connected to a Terminator.

Arnold hated the idea. I had the script, still warm from the printer, in my briefcase, made it to the plane where Carolco was flying a whole bunch of actors and directors to Cannes. Arnold reads it on the plane, and we have breakfast in Cannes the next morning. He had that look, that look I was talking about. ‘Look, Jim, I read it, it’s very well-written, but I don’t kill anybody.’ I’m like, ‘I know, that’s what’s so great about it! We take this guy who’s this monster and we make him a hero!’ He was aghast. He says, ‘Alright, but on page 40 John tells me I can’t kill anybody. I can machine gun people before that!’ I said, ‘Okay, you got me on a legal loophole. But you’re going to be the hero. The hero has to start and end as the hero. It’s only coincidence that you haven’t killed anybody up until then. You get reprogrammed by John verbally, and then you’re good. But are you really good, or are you just acting out good?’ He said, ‘Well, am I really good?’ I said, ‘That’s what we’re going to find out together.’ He was like, ‘You asshole!’ He and I really got along well, but he did have these moments of crisis where I’d have to kind of talk him down off the ledge. And it worked out.

Did he not recognise the potential power of, ‘I know now why you cry, but it is something that I can never do’?

It grew on him. I don’t want to say that he did it unwillingly. As we got into the process of making the film, he started to embrace it and figure out, creatively, what he needed to be all the way along. And at the end, there’s actually real heart.

Terminator 2 is also hugely about being a parent.

Exactly. And a child. In fact, I wasn’t a parent when I wrote that either.

So what prompted that?

Pretty simple. She [Sarah Connor] was pregnant at the end of the last movie. I don’t know how to write my way out of that corner. So it became a kid and his Terminator. The only question in my mind was, ‘Who’s the bad guy?’ What concept is worthy? My first idea was two Arnolds. The Battle Of The Equals. Then I thought back — my very first idea for The Terminator was that it was in two parts, not two movies, but a story where they [Skynet] sent their robot, and when they sensed on this chronoclastic wave that they had failed, they sent the one that they were afraid of. That they didn’t want to use, because it was so effective and so rapacious that it could really fuck up timelines. They sent the really scary motherfucker and the really scary motherfucker was the T-1000. And I couldn’t figure out how to do the T-1000. But that was in 1982.

“The lesson of Arnold is, ‘What’s that face telling you?’”

You eventually figured it out. But two things about the T-1000. This may be apocryphal, but I heard that you were thinking about Michael Biehn for the T-1000 initially. Is there any truth in that?

Zero. The only notion that I entertained seriously, up to and including doing a screen test, which I actually found recently — it actually exists — was Billy Idol. I was fascinated by Billy Idol’s physical look. I remembered the lesson of Arnold, and the lesson of Arnold is, ‘What’s that face telling you?’ He had a kind of sneering, sinister quality. It was a bit stylised, but in the right context, with the right direction and the right lighting, this could be interesting. Because the T-1000 didn’t have a lot of dialogue. So I tested with Billy and, actually, the test is pretty good. He had a little bit of a mannerism that he had perfected as part of his stage persona, a bit of a lip sneer thing that he did, that was inappropriate for the character. Maybe you’d resurrect it once towards the end, when he kind of becomes his own persona, where he’s not trying to be somebody else. I can’t say definitively that it wouldn’t have worked, but it was taken out of my hands. It also wasn’t like, ‘Yeah, solid, we’re doing this.’ I was still looking at other possibilities. I hadn’t met Robert [Patrick] yet, but then Billy got in a motorcycle crash and screwed up his leg, and he wouldn’t be able to walk without a limp. That didn’t work. So then I met Robert and once I met Robert, I really focused on him.

The second thing about the T-1000 is that the idea for it is so brilliant and so pure that the rest of the Terminator franchise has been trying desperately to top an idea that is really difficult to top. Maybe even you struggled yourself, Jim, to top the T-1000 in Terminator: Dark Fate.

It’s a little bit, I don’t want to say derivative, but to me it’s obviously iterative, in the same way that John’s now ten years old and Sarah’s his mom and she’s crazy. Those are obvious iterative ideas that are still solid narrative, right? To me, the obvious iterative idea is that you’ve got an endoskeleton that’s very advanced, and you’ve got the capability of the fluid, chameleonic, transformative power added to that. So to me, what we call the Rev-9 in Dark Fate is actually really cool. I like the Rev-9. I think the Rev-9 was cool as shit. Personally, I think that’s as good as anything that we did back then. But the film overall, our problem was not that the film didn’t work. The problem was, people didn’t show up. I’ve owned this to Tim Miller many times. I said, I torpedoed that movie before we ever wrote a word or shot a foot of film.

How come?

It went like this. I said, ‘I can’t sign up for a new Terminator movie without Arnold.’ And Tim didn’t want Arnold. Tim didn’t have anything against Arnold. He just wanted to create his own thing, which is a directorial choice, right? But I said to David Ellison, ‘Look, I don’t want that phone call from Arnold. You’re doing a Terminator movie without me, your friend of forty years?’ So either do it without me, or Arnold has to be approached, at least to make an offer. And so that played out, and now Arnold was on board. So we’re sitting in the writers’ room. ‘Alright, what are we going to do, guys?’ Explored many, many different ideas. Tim liked the idea of Sarah. I’m like, ‘Hey, I’d love to see Sarah come back.’ I’m getting high on my own supply and now I’m starting to think, ‘Oh, we’re going to do a legit sequel to Terminator 2, right? Literally what it should have been.’

We achieved our goal. We made a legit sequel to a movie where the people that were actually going to theatres at the time that movie came out are all either dead, retired, crippled, or have dementia. It was a non-starter. There was nothing in the movie for a new audience. I mean, a Terminator audience skews male. It skews young, 15 to 25. We had nothing in the movie for a young male. There wasn’t even an aspirational male character in the film. We kill off John, then it becomes a triumvirate of women, which I love. But it didn’t work. So, what’s on the poster? Linda at 60-something, Arnold at 70-something. This is not your father’s Terminator. This is your grandfather’s Terminator. People just didn’t show up. Is the movie good? I rate it as solid, yeah. Tim and I had our differences. Everyone knows that. We’re pals now. We were pals before — not during — and we’re pals now. We’re even talking about doing some more stuff together, just not in Terminator. We basically have a 100-metre restraining order for anything to do with Terminator. But he loves all the same stuff that I do, so we actually get along great. So that hatchet has been well buried.

But I just think we miscalculated the whole thing. We weren’t making a movie for where the audience was. You’ve got to meet the audience where they are. We just didn’t get bums in seats. It wasn’t the merits of the film. Because I think the film’s cracking. It’s ultimately not the best one. I still think mine are the best, but I put it in solid third. The other ones, to me, are discountable. I think they just missed it every time. There are glimpses here and there of coolness. I could tell you why each one of the other three sequels is flawed, but I don’t like to criticise other filmmakers’ work. I’ll criticise my own work. You can see, I’m pretty merciless.

“I can’t come in and be the saviour of the franchise if I’m not listened to, and I wasn’t a lot of the time.”

But as the father of the Terminator franchise, watching those movies from afar, what did that feel like, from Rise Of The Machines to Terminator Genisys?

Not my problem. It’s somebody else’s problem. It only became my problem again when I put my hand up and said, ‘Yeah, let’s do another Terminator movie!’, and I got my ass handed to me on that one. First of all, I can’t come in and be the saviour of the franchise if I’m not listened to, and I wasn’t a lot of the time, and then I was, but it was kind of too late. And by the way, all that stuff is irrelevant, because ultimately the decisions made at the very beginning, before we’d written a word of the story, were the death knell of that project. There’s a lesson there, and I think that lesson might apply to the Star Wars universe or the Marvel Universe. You get too inside it, and then you lose a new audience because the new audience care much less about that stuff than you think they do. That’s the danger, obviously, with Avatar as well, but I think we’ve proven that we have something for new audiences.

There’s certain things that are of the fabric of Terminator that have nothing to do with the Linda Hamilton of it all, or the Arnold of it. You’ve got powerless main characters, essentially, fighting for their lives, who get no support from existing power structures, and have to circumvent them but somehow maintain a moral compass. And then you throw A.I. into the mix. Those principles are sound principles for storytelling today, right? So I have no doubt that subsequent Terminator films will not only be possible, but they’ll kick ass. But this is the moment where you jettison all the specific iconography. If this is a spoiler, or reveal, or whatever, that’s fine. This is the moment when you jettison everything that is specific to the last forty years of Terminator, but you live by those principles.

This is your plan for the future?

It’s more than a plan. That’s what we’re doing. That’s all I’ll say for right now.

Let’s go back to the Terminator movies you made. After The Terminator, you moved onto Aliens pretty quickly. Had that not happened, would you have made Terminator 2 more quickly?

Probably. But the thing was, I didn’t own the rights. When Hemdale came along six years later and said, ‘So, you got any ideas for a Terminator sequel?’ Well, maybe, but I hadn’t really thought of it. I had distanced myself because I didn’t own the rights. They said, ‘Well, we got the rights’. I said, ‘Have you got Linda?’ Well, no. ‘Have you got Arnold?’ Well, we can make a deal with Arnold. ‘So you’ve got the rights, but you don’t have that much.’ And they said, ‘We’ll pay you $6 million’. I said, ‘Tell me more’. [laughs] It was a short conversation. We made a deal that was a half a page, single-spaced letter: ‘I, Jim Cameron, agree to write, direct and produce Terminator 2 for $6 million. Signed, Jim Cameron’. Then sometime in post, a 60-page contract showed up, and we started negotiating. The movie had already come out and made $500 million before I actually signed the contract.

You’re kidding.

No, that’s how Hemdale were. My kind of guys. They did not waste time on bullshit. The last thing they wanted to do was make lawyers rich. So we just did it on a handshake. I love those guys. So I said, ‘I’ll go get Linda, you guys get Arnold. Pay him a shitpile. I’ll go talk Linda into it, if I can.’ She was my first phone call. I said, ‘You got to make her deal first, because I certainly can’t write a word until I know whether she’s in or out’. I just took Arnold as a given. They were going to go offer him a shitpile, and he took it. He wanted to do it. I knew he wanted to do it. I didn’t know where Linda’s head was at. She was pregnant and working on something in North Carolina. I wound up flying down there and having dinner with her. And she said, ‘Okay, yeah, I guess, but it’s kind of in my rear view.’ I said, I know, I said the same thing. She said, ‘One thing I want you to do: I want to be crazy.’ I said, ‘How crazy? ‘Like, institutionalised crazy. Straitjacket crazy.’ I’m like, great, that works, perfect. So that’s where that came from. Here’s mom, here’s the son. The son doesn’t believe the mom. Why doesn’t the son believe the mom? Because she’s in a mental institution. This was all falling into place. That’s why the only big decision was what to do with the bad guy.

But you know, I give credit where it’s due. This idea that there’s this auteur, and everything springs fully formed from the forehead of the auteur, I think it’s bullshit. It’s collaborative. You ricochet off of other people and their creative impulses. Linda played that to the hilt. But was Sarah really crazy? No, the big irony is, she wasn’t crazy at all. She was perceived to be crazy by a system, a mental health system. You know, most shrinks are crazy, they just get to be in the power seat. It’s all about power. Cops have power. Military people have power. Psychiatrists and psychologists have power, right? It’s all about puncturing the power structures, which the main characters have to do to survive. They have to circumvent them. The power structures don’t help them. That’s one of the appeals of both Terminator 1 and Terminator 2. I think they miss that little factor in subsequent films.

Was there ever a scenario where you would have directed a third Terminator after T2?

I think if Carolco had held the rights. But Carolco collapsed shortly thereafter. If Carolco had held onto the rights, I think they would have come to me. I mean, they did. They sort of lost it, they went bankrupt and then they circled back around and got them again. But in the interim, I wound up going my own way and doing other things. But if there had been a continuum, maybe. It’s a maybe, because it just never came up.

You never had a decision to make.

Eventually, Andy Vajna and Mario Kassar, their companies dissolved, but they formed new companies and then they got together and reacquired the rights. They called me up. I was finishing Titanic at the time and was like, ‘Guys, I’ve moved on. I’m doing this other thing. I can do anything I want at this point. I don’t have to be stuck in the past’. That’s what I said. I was also pissed off at them because they went and got the rights and they didn’t consult me. They didn’t talk to me ahead of time. They just went and got it and then assumed, because that’s how they played – which was always very, very fast and loose – that they could just buy me after that. At that point, I was playing a game more from principle than from money. You can’t just buy me. You should have asked me if I wanted to be a partner with you guys, but you didn’t. And we were pals, and now we’re not pals.

I didn’t even speak to Andy Vajna for, whatever, 20 years after that. And he and I had been close. I was never that close to Mario. I liked Mario, but Andy and I had gotten close. We used to ride motorcycles together. But that pissed me off, so I just kind of went my own way and said, ‘Guys, go with God.’ Eventually we patched things up because I just thought it’s not worth holding onto grudges forever. I’m glad because he wound up dying a couple of years later. We didn’t carry that to the end.

So, Arnold never asked you to think about it?

When Arnold got approached for three, he said, ‘They want me to do this.’ I said, ‘Well, you should do it.’ He said, ‘Well, I want to make sure it’s okay with you. I won’t do it if you’re not okay with it.’ I said, ‘Well, first of all, this character is as much your character as it is mine. I may have created it, but it’s you now. You own it more than I do in the zeitgeist, in the public imagination. I’m not going to hold you back as a friend. But I want you to do one thing.’ He said, ‘Sure, anything.’ I said, ‘Get all the money.’ He said, ‘Well, what do you think?’ I said, ‘I’m seeing a number that starts with a three’. He said, ‘Really? No way!’ I said, ‘Way. Ask for 30’. And he did, and he got it. That’s the kind of pals we are.

Did you get 10% of that, Jim?

I should have. Shit, I was his agent right then.

Let’s talk about landmarks. There’s a couple that you created. One is 2029 — both your Terminators open in 2029, and you had a pretty dim view of humanity’s future.

Well, we can still hit that one.

We’re five years away. There’s every chance.

I think the US has got 3000 nukes that are in the 1-5 megaton range. The Russians have that, and a little bit more. We can still hit that one easy. You look at all the sabre-rattling and sheer human stupidity, it’s like we haven’t learned a goddamn thing. We’re not evolving. So maybe AI can come along and help us.

The other landmark is August 29, 1997. What did you do on that day? Did you celebrate it in any way?

I think it came and went without me thinking about it. But there’s a very interesting story about that. I made that date up out of whole cloth. Just picked the date. The story was written in 1990, so I just set it out a few years. I figured, seven years is enough and I just picked a date out of thin air. Then I thought, ‘Alright, I gotta come up with some bullshit news story that makes it like the most innocuous day in history. What’s your headline?’ So the headline had to be something — not war breaks out or some major event, but a super minor event. Michael Jackson’s 40th birthday. I pulled that out of my ass. Guess what Michael Jackson’s 40th birthday is?

You’re kidding me.

What are the odds? That’s when I got spooked, because I didn’t find that out until a couple of years later. I think I might have been off by a year. But that’s actually his birthday. I think it was his 41st or something like that. Or 39th. But I made that shit up and it turned out to be true. It’s not like I looked it up and chose that. I’d love to say that I’m like some eidetic super computer that reads a fact once… I can’t remember shit half the time. I can remember every detail from every movie I’ve ever made, almost down to take numbers. But I can’t remember what I read in the paper yesterday. Broad strokes but not details.

It was probably something depressing about how we’re all going to be dead by 2029.

I’ve got five years to head that one off.

Speaking of dates, in The Terminator, when Kyle first appears he grabs the cop and says, ‘What day is it?’ The cop says, ‘Thursday. May 12’. So that would suggest that most of the rest of the movie takes place on Friday the 13th.

[laughs] I never thought about that.

So that wasn’t deliberate?

I don’t know if May 12 is even a Thursday. I certainly didn’t take time looking any of that stuff up. As for Friday The 13th, I never really thought about that. It is a slasher film, ultimately, though I think it owes a lot more to Halloween. The idea of the implacable monster that can’t be killed, and multiple endings, and the last girl. My original drawing for The Terminator, my original art, he had a knife in his hand, not a gun.

And he sits up in the background, like Michael Myers.

Hell yeah, absolutely. But look, John Carpenter and Debra Hill — Gale and I fancied that, in wild success, we would be them. Seriously, that was our reference point. We were working for Corman, Carpenter and Hill had essentially become their own Corman. They had created their own independent success. They were guerrilla filmmaking icons to us. It’s only later, in retrospect, I realised what tiny players they were in the grand eco-system of Hollywood. But Halloween has huge, huge, lasting impact. That was our reference point. To me, Terminator was just a science-fiction version of Halloween.

A version of this article was originally published in Empire’s November 2024 issue. Order a copy online here.